My So-Called Career/5

Trainer and Author

Think Tank, Brainstorm, and BPMessentials

In the mid-2000s, I had these BPM reports to sell, so I hooked up with a company called Brainstorm Group, who was starting to put on a series of BPM conferences around the country, four a year: Chicago, San Francisco, Washington, and New York. Most of the speakers were on the process improvement side, but I would speak there about the technology, the components of what Gartner was now calling a BPM Suite, as a way to market my reports.

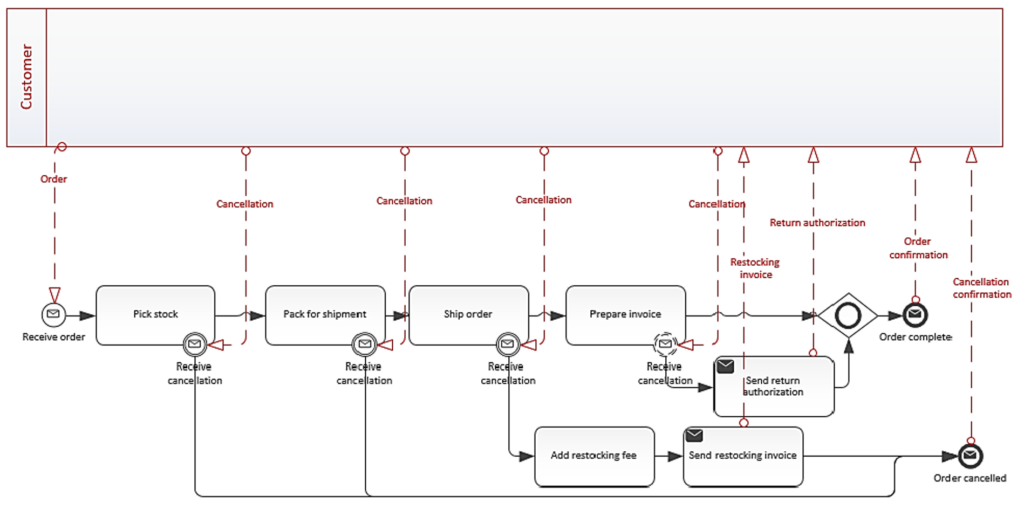

In those conferences I would talk about BPMN in the context of process automation, but it turned out the attendees didn’t care at all about automation. BPMN users simply wanted to document how their current state process worked, maybe analyze it for improvement using Lean or Six Sigma methodology. I admit I didn’t really understand that.

And there was a problem on the automation side, because BPMN and BPEL were not precisely matched. There were things you could draw in BPMN that BPEL could not execute. A strange situation evolved in which many new BPM products used BPEL execution but graphical BPMN modeling, putting complicated constraints in the diagrams the tool would allow. This was not good; it needed to be fixed.

By 2005, BPMI.org was in trouble. BPMN was popular, but BPMI.org did not own BPEL, the execution language. To discuss the situation, they hosted an open-ended meeting called Think Tank in Miami for members and others interested in keeping BPMN alive. At the last minute their keynote speaker, someone from Gartner, cancelled, so they called me. I was surprised but happy to go.

In my keynote, I was supportive but maybe in a cranky mood. Ever since my fax binary file transfer experience in 1988 I had a lingering distrust of standards organizations. The incompatibilities between BPMN and BPEL were not being addressed. I thought BPMI.org was blowing it and I let them know. They still had no XML serialization of BPMN (other than the obsolete BPML) and no defined mapping to BPEL, the executable language. They needed to get these done! What were they waiting for? In truth, they were waiting for a financial lifeline, which came from the Object Management Group (OMG), another standards organization. OMG would take over BPMN from BPMI.org, although they did not seem to be in any hurry to address the issues I raised.

The meeting overall had freeform discussions about many topics, and all the major participants in BPM were there. It was great. In fact, that Think Tank meeting became legend, and years later I would try to recreate something like it.

Think Tank was also where I met Stephan Fischli of Bern, Switzerland, whose company itp commerce made a BPMN add-in to Microsoft Visio. Back then, the free BPMN tools from automation vendors didn’t follow the spec, since their real job was funneling users into their proprietary executable design software. But itp commerce just did the modeling not execution, and their tool was faithful to the spec. At that time, other people were publishing on their websites free information about BPMN, almost all of it dead wrong. Stephan’s tool had validation rules to check for incorrect models, which I liked very much. When BPMN 2.0 ultimately came out, itp commerce was the first tool to fully support it.

I had recently had lunch with an ex-BPM guy named Rodrigo Flores, who told me I could make serious money doing BPMN training. That idea had never crossed my mind and I wasn’t sure I believed it. Until then, the bulk of my clients and report customers had been technology vendors, not end users. On the other hand, while vendor business always declined sharply as a technology began to mature, the end user business would continue to rise.

At Think Tank, Stephan and I decided to start a joint venture to do training in BPMN, the modeling notation. We called it BPMessentials. The training would be recorded video and offer post-class certification. For groups we also offered live onsite training. His company would provide the tool and the web infrastructure for e-commerce and hosting the videos; I would provide the course content, which he was authorized to deliver in German. Regardless of who gave the course a portion of the fee would be contributed to the infrastructure (meaning actually to itp) and the balance would be split 50-50. We launched BPMessentials in February 2007.

As a training provider, I had a new proposal for Gregg Rock, the head of Brainstorm Group. He was starting a related business called BPMInstitute.org, which would provide training at his conferences. I would provide BPMN training, give BPMInstitute exclusive rights to sell my BPM Reports, and contribute a monthly column to their newsletter. The training deal was the key. He would market and host the events and provide the A/V, handouts, and food. I would provide the course content, delivery, and certification. We agreed on a fixed price off the top to Gregg to cover his cost and a split of the net revenue. My training deal turned out to be better than the one he offered to other training providers. The reason is that the other “training” courses were just teasers for engagement consulting. For the “trainers” it was just marketing for their real business. My course was different, not a teaser. I was teaching students how to do process modeling themselves, for real.

Eventually that deal became a problem. After a few years, Gregg delayed paying me my share, then stopped paying altogether. In the end he probably owed me $25K. I stopped contributing the monthly columns. I stopped doing the training at his events, obviously. I had a Massachusetts lawyer (Brainstorm was based in Mass.) send him threatening letters, all to no avail. Eventually I settled for something closer to $15K. Fortunately, in all my years of self-employment I have almost never been unable to collect money owed by a client. Gregg Rock stands alone. He owes money to everyone who has had dealings with him.

Despite the issues with Gregg Rock, BPMN training via BPMessentials became my main business, much to my surprise, and the decade 2008-2018 was the most financially rewarding. The training was provided in a variety of formats: web/on-demand (recorded videos), live-online, and live-onsite, the latter two for groups only. I was traveling all the time, although I greatly preferred the web/on-demand format.

Toward the end of that period I began working much more with Trisotech, another tool provider, although the BPMessentials partnership with Stephan continued. His company was purchased by the Swiss IT Services company ELCA in 2023, and I recently concluded the sale of rights to the BPMN training to them. The impetus for the switch to Trisotech was my involvement in the wider world of business automation standards… something I am actually best known for today

BPMN 2.0

When OMG took over BPMN after Think Tank in 2005, they seemed in no hurry to finish BPMN 2.0. It turns out they had “other plans” for BPMN. OMG’s original mission was to develop standards in the area of “business objects”, a method of distributing program functionality across different systems in a network, and to promote something called Model Driven Architecture, a way of generating code from object models. BPMN really had nothing to do with business objects. It was more aligned with the newer service-oriented architecture. But the “old guard” at OMG secretly wanted to take an existing OMG project, called Business Process Definition Metamodel (BPDM), and, since BPMN was already quite popular, simply rename it BPMN 2.0. I would describe these old guard folks as head-in-the-clouds professor-wannabe types, not active participants in the industry. BPDM was not a concrete language at all, and it had almost nothing in common with BPMN 1.x, which was in widespread use. It was doomed to fail. But OMG’s attitude was, we own it now and we’re doing it.

Organizations like OMG have formal procedures for creating new standards. There is an RFP setting out the requirements, submissions that fulfill the requirements, a draft specification, and then a final specification. Normally there is only one submitter, but with BPMN 2.0 there was a revolt. In addition to BPDM, there was a rival submission from the team of IBM, Oracle, and SAP, three of the biggest software companies on the planet. They had no interest in BPDM. They needed BPMN 2.0 to fix the problem I had called out at Think Tank. They needed BPMN 2.0 to be a language that could execute the BPMN notation.

Although they started late, the IBM team easily overwhelmed the old guard proposal BPDM. When they published their first draft submission in the fall of 2008, it was actually the first time I’d heard about it, even though I had been doing BPMN training for a year and a half with BPMessentials. The draft was interesting, but one section, on events, was written in a very confusing way. As a comment, I rewrote it in a less confusing way and sent it to them. In response, they said, if you want us to incorporate these three paragraphs, you’re going to have to sign this contract and fax it to us. That seemed like an oddly formal procedure for a comment, but what I did not realize was this was an invitation to become a member of the IBM team vying to beat BPDM as the candidate for BPMN 2.0.

Ultimately BPDM threw in the towel and the IBM submission became the basis of the BPMN 2.0 beta spec. I was on the task force drafting the spec, the other members of which were architects from IBM, Oracle, and SAP. This took six more months. The sole focus of the task force was making process models described by BPMN diagrams executable on an engine. The BPMN 2.0 notation – the shapes and symbols in the diagram – were mostly the same as in BPMN 1.x, but now they would be formally described by a metamodel (UML class diagram) and equivalent XML schema that would contain many additional elements – not visualized in the diagram – specifying executable details.

Oddly, few if any of other task force members had been users of BPMN 1.x previously, so it fell to me to be the voice of existing modelers – who were non-programmers – in BPMN 2.0. Since there would be minimal changes to the shapes and symbols, I wanted to ensure that diagrams that had always been used in BPMN 1.x would still be valid in BPMN 2.0. One time, I recall, some execution-related detail was defined as Required in the schema. I complained that since it was not in the diagram and only used in execution, it would be omitted in non-executable models, which would make them schema-invalid (something you definitely don’t want). And the committee’s response was, So what, we don’t care. On that occasion I had to pull strings with a Senior VP at SAP, a guy I had helped to sell his workflow company to Lotus a decade earlier, and we got it fixed.

The draft BPMN 2.0 spec came out in the summer of 2009. It would require another year of work by the Finalization Task Force and then months of God knows what by OMG to become a final spec, but I was already worn out. Being on these standards task forces is hard work. There is a conference call every week, writing up issues and proposals in between, and lots of arguing. I did not continue with the FTF, because I had something more important to do concerning BPMN.

Cody-Cassidy Press

The audience for the BPMN spec is not process modelers or programmers but “implementers,” meaning vendors of BPMN tools. Consequently, the spec is not a tutorial on process modeling, but rules for software vendors to ensure their tools are conformant with the standard and, ideally, interoperable with each other. To that end, the language of the spec is often obscure and even misleading to the uninitiated. Also, because BPMN 2.0 is the work of a committee, it contains many elements that are never used in practice and have no business being there at all. But to the outside world, the spec is all the information they have.

I knew from a couple years of doing BPMN training that what was needed now was a book that cut through the clutter and obfuscation and explained clearly which elements you need and which you don’t, and how to do process modeling correctly using BPMN 2.0. That book, BPMN Method and Style, together with its subsequent editions and the tools and training based on it, became the thing I am best known for today.

I decided to publish the book myself. I knew that was possible because Peter Fingar, author of BPM: The Third Wave, told me how he had done it, naming his imprint after his kids. I named mine Cody-Cassidy Press after my dogs. The book Aiming At Amazon explained everything I needed to do. I did not need a copy editor or layout designer. I could do that myself. My sister Katy would design the cover. To produce the books, I used LightningSource, the print-on-demand subsidiary of Ingram, the largest book distributor in the world. I do not get a royalty; I am actually the publisher. After subtracting the printing cost and the distributor discount (25%), I got all of the money… and it was a better deal than the one from Amazon’s Kindle Direct Publishing. (Today the deal is not nearly as good, as the distributor discount now must be at least 40% and printing costs are much higher.)

Becoming a self-publisher was actually easy to do. You need to purchase id numbers called ISBNs, and I recall the price for 10 was a little more than the price for 1, so I bought 10. I never thought I would use them all up, but a few years ago I actually did.

BPMN Method and Style came out in the summer of 2009 based on the draft BPMN 2.0 spec. A second edition came out in 2011 based on the final spec, and added an implementer’s guide focused on the metamodel, XSD, and execution-related details. The second edition is available in German, Spanish, Russian and Japanese editions, as well as English. To me, it’s too long and out of date with respect to my current training, but it still sells today and is used in many college curricula.

Method and Style

I didn’t want BPMN Method and Style to be just a summary of the BPMN 2.0 spec. Because I was on the drafting team, I knew the details ahead of other folks so I was confident my book would be first, but I also knew there would in time be lots of other books and free online information that would simply summarize the spec. But if you simply summarize something long and incomprehensible, you’re not creating anything useful. I wanted my book to be useful.

At that point I had been doing BPMN training (based on version 1.x) for over two years. I knew which elements were important and which were never used. I knew the things that students understood easily and which parts were totally confusing. I wanted to provide a prescriptive methodology for using BPMN in the real world.

For process modelers, the real world was about documenting and improving their processes using diagrams. It had nothing to do with automating them in an execution engine, which was the primary focus of the BPMN 2.0 spec. I already mentioned my battles with the committee about which elements should be required and which optional. Actually, most elements in the spec had no visual representation in the diagram at all. Their values were entered by programmers as they made the diagrams created by modelers executable. To see them you had to look in dialog boxes inside an executable design tool.

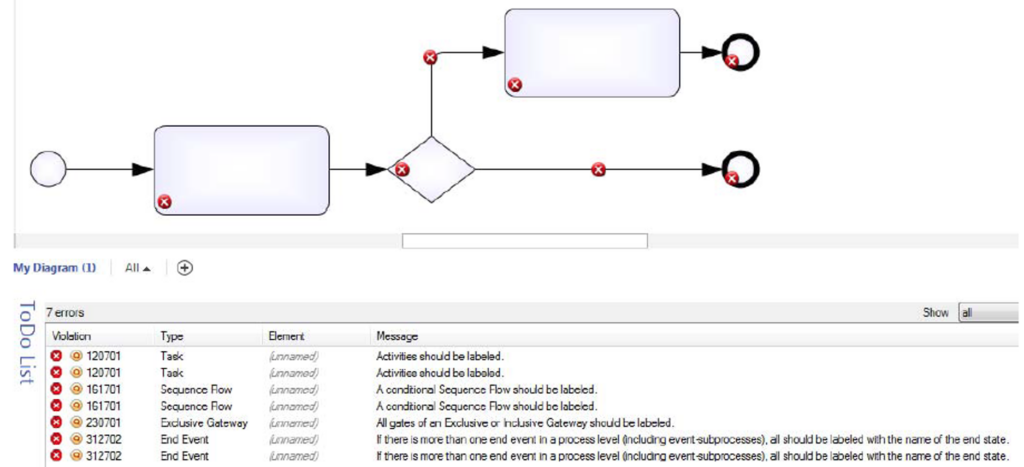

That was useless to most modelers. A key principle of Method and Style was, from the start, if it’s not in the diagram it doesn’t count. You might say that’s obvious, but one element the spec did not require was the label on the various shapes and connectors. And while the spec defined icons inside some of the shapes to describe them more specifically, models were not required to display them. The spec defined connectors called message flows to show how information flowed between the process and things outside the process, but you did were not required to show them, either.

Simply put, the only things the notation provides modelers to communicate meaning are the basic shapes and connectors displayed in the diagram, the symbols you can put inside them, and their labels… and use of the latter two were not required by the spec. So making BPMN useful to modelers needed additional rules beyond those in the spec, rules that required icons and labels and rules that required the count of certain elements and the values of certain labels in one diagram in the model to match those in another diagram. I called them style rules, and I simply made them up. Someone had to do it!

In addition, we needed a modeling methodology, also not covered by the spec. The Method is a prescriptive methodology for taking the information about how a process works – typically gathered in stakeholder workshops and interviews – and translate that into models that communicate the workings clearly and completely through the diagrams alone. It doesn’t tell you how to conduct those workshops or how to improve your process. Plenty of process improvement methodologies cover that. It simply provides a step-by-step approach to organizing the information so that its representation in the diagram is clear and complete. BPMN Style is a set of rules, in addition to those of the spec, intended to make the meaning understood clearly and completely through the diagrams alone. Method and Style is not about automation or process improvement. It’s simply about communicating meaning through diagrams.

What made the style rules work in practice was the itp commerce tool, which included them in its automated validation. That didn’t happen until around 2010, but it dramatically improved student learning and saved me a lot of time reviewing students’ certification exercises, which had to include no violations of either spec rules or style rules. Most of the errors were simple things that could be caught be automated style rule validation. Once that was in the tool, I required students to validate and fix all the style errors before sending me their models for review. Post-class certification was the critical competitive advantage of my BPMN training, and style rule validation made it so much easier to do.

Later on, two other tool vendors, Signavio and Trisotech, added style rule validation to their tools, and I began to use them as well for BPMN Method and Style training.

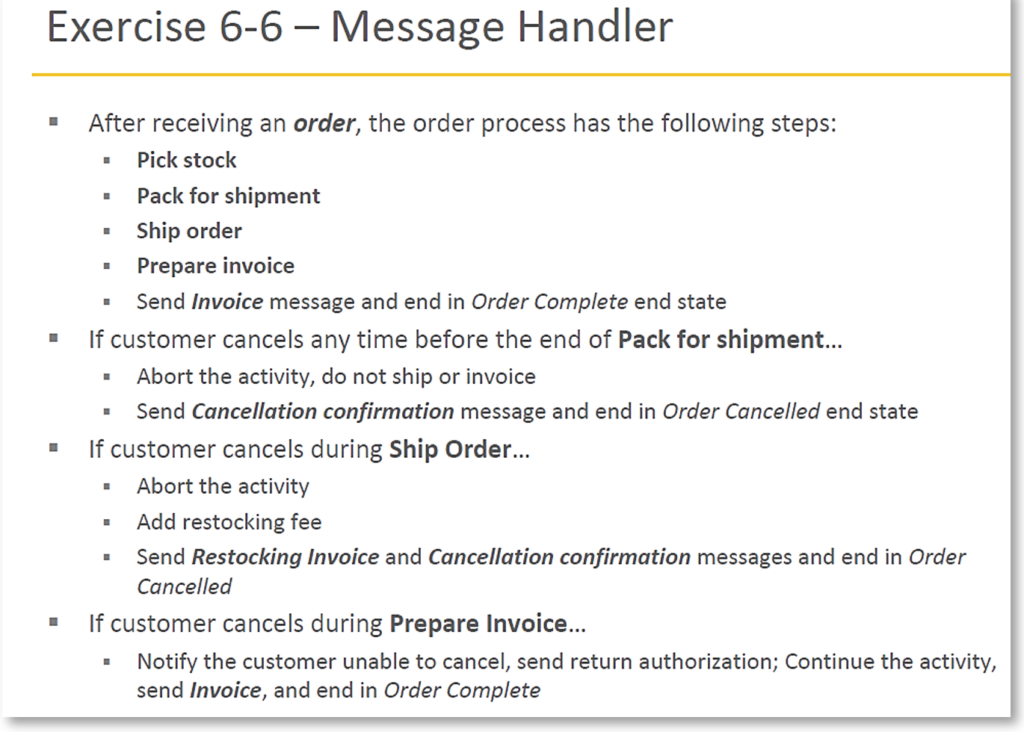

Method and Style Training

The methodology and style rules in the book became the centerpiece of my BPMN Method and Style training. They say those who can, do, and those who can’t, teach. Maybe that’s so, but Feynman also says if you really want to understand a subject, you need to teach it, and I can say from experience that’s definitely true. Students ask questions, many of them dumb. It’s thinking about the dumb questions that gets you to re-examine things you took for granted, on occasion resulting in new insight.

I trained over 7000 students in BPMN using Method and Style, answered many dumb questions and gained many new insights. Through that, I came to see that many of the most basic concepts of BPMN are never discussed at all in the spec. They are unspoken, simply assumed to be obvious, or more precisely, obvious to a process automation programmer circa 2008. My training explained those things. Through the process of training students I gradually moved from “This is what the spec says…” to “This is what this element really means…” I also moved from “The spec says you can do it this way or this other way or this third way…” to “Always do it this way.” Students don’t want choices, they just want you to tell them how to do it. Over the years I continually pared down the number of diagram elements to use and tried to make process modeling as simple and mechanical as possible. I always start by telling students modeling is not a creative exercise – process improvement is a creative exercise, but modeling is just a discipline. It sounds pedestrian and boring, I know, but it’s exactly what is needed.

I was always one who could learn from books. In physics, you have to be able to do that. But most people cannot do that. They need training, with exercises and feedback. That’s a good thing, because the income from training greatly exceeds that from books. In my earliest books, like BPMN Method and Style, I would start with the book, then bring examples from the book into the training, where I could see from experience which parts worked and which did not. That let me continue to evolve the training and ultimately write a much-improved second edition book based on the evolved training. Eventually, I learned it’s better to start with the training and then write the book. In 2017, I did just that with a follow-on book called BPMN Quick and Easy, much shorter and aligned with the training. I wrote it in my spare time on a short vacation, and I think it’s my best BPMN book.

The key difference between books and training are exercises that students have to do themselves in the tool. You show the student how to do X. Any questions? There are none. Then you ask the student to open up the tool and do X themselves. Ha! That’s much harder. OK, here’s my solution. Does yours look like this? No, it does not. That’s ok because we’re going to keep doing this.

There is a lot of material to cover, two full days in the onsite training, at the end of which the students’ heads are spinning. And that’s ok, too, because the training includes use of the tool for 60 days in order to complete certification, which is based on an online exam and a mail-in exercise that they must iterate until it is perfect. When the student finally completes certification, he or she is a semi-competent modeler. Before that, no.

In the early days, much of the training was for groups onsite, usually back East or in the snowy Midwest. The traveling got old real fast. For several years I did public live/online training every other month, live training delivered over the Internet. That needs 8 or more students in a class to make it worthwhile, so as demand declined a few years ago I stopped doing it. In addition, I always also had recorded video training, available on demand. Back in 2007 I used a program called Camtasia, which was super labor-intensive; if you had a typo in a slide you had to completely re-record the audio in that slide. Later on I moved to Articulate Storyline, which lets you just add audio tracks and screencams to Powerpoint, so producing the videos went much faster.

Storyline is a very interesting product because you can program complex student interaction with the slide. In 2015, I had been using a free iPhone app called Duolingo to learn French and thought I could use Storyline to create something like that to teach BPMN Method and Style. Duolingo is 100% quiz questions, no “lecture”. You learn by making mistakes. Back then, “gamification” was the big thing in online learning. You make it a game, with levels and badges and stuff. I know, Millennials! Anyway, I was looking for a way to teach the course for less money, no tool or certification.

The result was a program called bpmnPRO. It cost $199 (or $50 for students in the training), a lot less than the $1000 or so cost of the training and certification. It reduces Method and Style to its barest essentials, matching the diagram to a text description of the behavior. It forces students to be very precise in the wording of the behavior and look very closely at the diagram to find the match. Like Duolingo, it is 100% multiple choice questions and puzzles and teaches everything we cover in the training. I still sell it today. In fact, it was used in a class at University of Georgia.

Until last year, I always managed to get one or two training classes in Europe, which was always a better BPMN market than the US. I did 4 classes in Netherlands, 2 in Paris, 2 in Copenhagen, Milan and Lake Como. In many of these, Junell would come along and we would make an extended vacation of it. We liked Europe a lot and would go there even if we couldn’t find a client to fund the travel.

methodandstyle.com

When Stephan Fischli and I started BPMessentials in 2007, I needed the web infrastructure that itp commerce provided, and I was fine with paying them $125 per student plus 50% of the video training revenue. Also, they were the only tool that had the style rule validation built in. Around 2013, however, I began to work with a second tool vendor called Signavio. Their tool was browser-based so there was nothing to install, which solved a problem for some of my clients. They agreed to implement the style rule validation in their tool and provide my students 60-day use of the tool for training, all at no cost, a better deal than I had with itp. I began to use Signavio as an alternative to itp commerce for live/online and live training, but not the web/on-demand. Back then we were trying to promote the BPMessentials brand, so the Signavio-based training was offered as an alternative on the itp-hosted website, which I’m sure caused them some discomfort.

Later I used Signavio for DMN also, a new decision modeling standard that itp commerce did not support. It made no sense to bring that under the BPMessentials umbrella, so I sold it on my own BPMS Watch website. By then my own site had e-commerce, and since bpmnPRO I had been using a third party online learning management system Scormcloud to host the videos. So I did not need itp commerce to provide infrastructure for me any more.

Then I began to do a lot more with a Montreal-based company, Trisotech, who had great cloud-based software for BPMN, DMN, and related things. At that point, I decided to relaunch my own site as methodandstyle.com. The name BPMS Watch no longer made sense – I wasn’t a BPM industry analyst any more. I still sold itp-based training on BPMessentials, but Method and Style using Trisotech had become my primary “brand”.

bpmNEXT

Around 2011-12, I was still attending BPM conferences giving talks about the value of BPMN and the need for training. I came to really hate those events, selling stuff to clueless newbies. It was a necessary evil, I guess, but I went to one that year that pushed me over the edge. It was called PEX, and everything about it – the attendees, the other presenters, the products in the exhibit area – was so stupid I couldn’t stand it. Also, it was in Orlando, never a good thing. At those events I used to hang out with the other BPM analysts, and after a few glasses of wine I started ranting about it and the kind of BPM conference I would want to go to instead.

It would be a bit like Think Tank back in 2005, not for newbies and not even for selling at all, but a peer-to-peer event for industry leaders where we would discuss where things were headed, where the technology was going next. I’d call it bpmNEXT. One thing I especially hated about typical BPM conferences were the “case studies,” talks by end user organizations about their experience implementing a solution by Vendor X. These were typically pay-to-play slots purchased by Vendor X as part of their conference sponsorship. Just awful. We would have none of those. In fact, I didn’t want those pie-in-the-sky TED-talk things, either. I wanted to see real working demos, stuff from the labs. I got pretty excited about it – too much wine, maybe? – but Connie Moore of Forrester (she had taken my place at BIS Strategic Decisions when I left in 1994) dissed the idea as “boys and their toys.” Well, whatever. After the event, Nathaniel Palmer said he liked the idea and wanted to partner with me in making bpmNEXT a real thing.

Nathaniel was also an independent BPM consultant/analyst. He had a lot of experience in putting on conferences, and he had recently purchased the brand BPM.com as a small media company. We wanted to make the attendee experience unique and were determined to avoid the typical conference hotel environment. At that time, I was living in Aptos on Monterey Bay, and we selected Asilomar, an iconic rustic conference center just off the 17 Mile Drive in Carmel. The buildings were designed by Julia Morgan, architect of San Simeon (and my sister Amy’s house in Piedmont). That first year, 2013, they let us bring our own wine, great for us but a mistake they would not repeat. We had about 60-70 attendees, chief architects and CEOs from BPM vendors all over the world. It was a fabulous experience.

We did it at Asilomar again in 2014, after which we decided to move it to Santa Barbara, where the environment is still beautiful but less rustic, and the food is a lot better. We did it there at the Canary Hotel off State Street downtown every year until 2020, when COVID killed it. We had meals on the roof deck, a Santa Barbara wine tasting, and it was just great. The size of the group was always about the same, and we had folks from 15 countries in the last one. There were a few analyst keynotes but it’s still almost entirely live demos. To limit the Powerpoint, SandyKemsley suggested requiring Ignite, a format using 20 slides that advance automatically every 15 seconds. Initially presenters hated that, but the audience as a whole loved it, so we continued to do it that way. bpmNEXT did a little better than breakeven, but making a lot of money on it was never the goal. It is still universally acknowledged as the best conference experience in BPM.

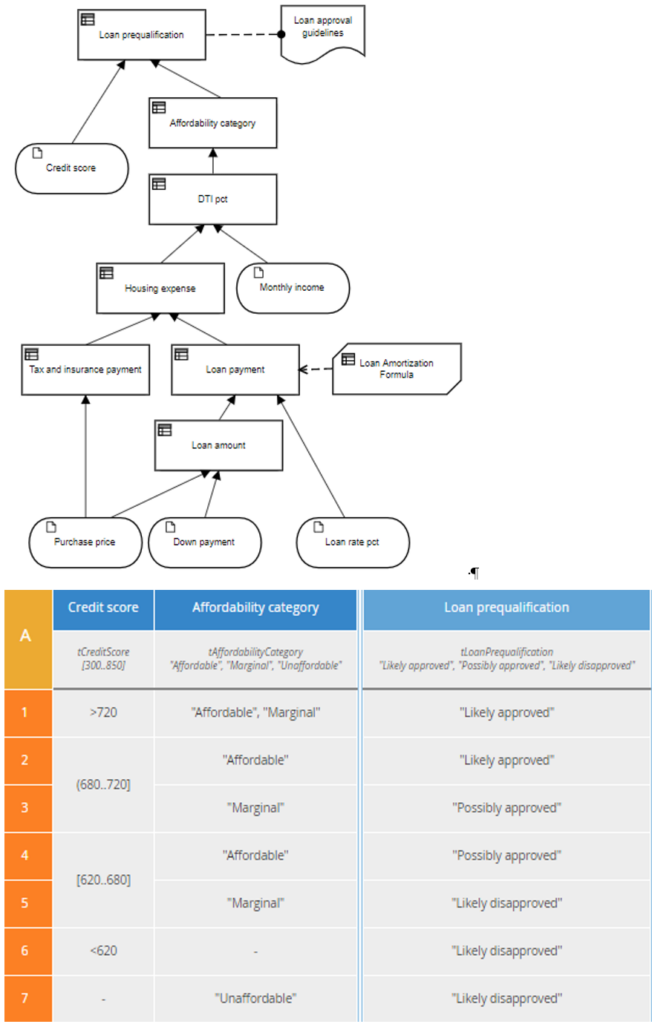

DMN

At the Brainstorm conferences back in the mid-2000s, one of the other consultants who offered training was Larry Goldberg of Knowledge Partners International. They had a methodology for decision modeling using business rules. This was a discipline completely different from process modeling but often associated with it. Process models describe the sequence of activities – actions – in a business process. Decision models describe the rules that comprise the logic of a business decision, such as should the loan application be approved? Approval of a loan at a bank, for example, involves both a process – a sequence of activities – and a decision, explicit logic based on rules.

Larry and his business partner Barbara von Halle later refined and patented their methodology, called The Decision Model, and sold their company to Sapiens, an Israeli software company, who made a tool to implement it. Part of their methodology involved process modeling, and Larry very much liked the discipline of BPMN Method and Style. Around 2012, he brought me into his client Freddie Mac, still digging out from the real estate meltdown, to do BPMN training. Afterwards he said Freddie needed me as a consultant, got me to take an overnight flight to DC to pitch it the next day, which I did, but to no avail.

A few years later, I began to read about a new OMG standard called DMN, Decision Model and Notation, that seemed a lot like The Decision Model. Larry, now part of Sapiens, had been part of the planning for DMN but his patent got in the way. OMG standards had to be open not proprietary. When it came out, the DMN 1.0 spec was confusing, as all OMG specs are, and I began to ask questions about it in an online forum. Gary Hallmark of Oracle provided answers, but as I looked at the schema I could see it was completely messed up.[23] In fact, if you simply open the DMN 1.0 XSD in XMLSpy, immediately the tool would go ding-ding-ding, invalid!! So, obviously, no one on the crack DMN 1.0 team at OMG had ever done something as basic as opening the schema in an XML editor.[24]

[23] My experience with XSD and XSLT, which began with EFAST2 in the previous decade, proved invaluable both for understanding BPMN 2.0 and DMN.

[24] All Java guys, obviously. As a rule, Java guys have no clue about XML but don’t realize it.

When I pointed this out to Gary, he let me know that he was actually the head of the DMN 1.1 Revision Task Force in OMG, and why didn’t I join it? So, just as I had with BPMN, I joined the DMN standards committee mostly by accident. My main contribution to DMN 1.1 was to fix the XSD and metamodel, which finally allowed DMN models to be implementable.

Like BPMN, DMN was designed for use by modelers on the business side who were not programmers. But unlike BPMN, DMN models – defined by non-programmers using diagrams and tables – were intended to be executable on a decision engine.[25] That was a significant difference. Still, most DMN tool vendors just implemented the basic diagrams of DMN, expecting the models to be used as “business requirements” handed off to programmers for execution using a proprietary language. In a way, that was how BPMN had always worked for executable processes. But DMN supposedly was taking an additional step, making executable design accessible to non-programmers.

[25] BPMN expected programmers to add execution details to the model in elements not displayed in the diagram.

DMN did that in two ways: First, instead of code, the “program” was defined by diagrams and tables. Second, the text in the table cells would use a new business-friendly expression language called FEEL, which was defined in the DMN spec. One thing that supposedly makes FEEL business-friendly is the fact that the names of variables can include spaces and punctuation, things definitely not allowed in normal programming languages. But that also makes FEEL very difficult to parse and compile for execution. Partly because of that and partly to avoid having to change their existing proprietary languages, most decision management vendors elected not to implement FEEL or the more advanced DMN tables. They would claim to conform to the DMN standard while just implementing about 5% of it.

Thus, as work progressed on DMN 1.1, there were just a few tools supporting DMN diagrams and decision tables, and none at all supporting FEEL. In my BPMN training, I had earlier begun offering a version based on an alternative browser-based tool from a German company, Signavio, and in 2016 Signavio was one of the first to support DMN. I quickly set about using Signavio in my new DMN training and book, DMN Method and Style.

In 2016 the DMN book and training filled a need, as there was absolutely nothing else available, but I came to regret both of them. As Intalio had learned the hard way in 2003, in tech it’s possible to be too early, and with DMN Signavio certainly was. Technically, FEEL was required even in basic decision tables, but Signavio used their own expression syntax, and they omitted support for DMN’s other standard table types. That limits what you can do, but Signavio had some big initial customers, like Goldman Sachs, who needed more advanced functionality. Signavio added what their customers wanted but wound up with a tool that did not follow the spec. Moreover, since their models were still not executable, there was no good way to check both the syntax and the logic. That means some of the examples in my book were incorrect. All of these factors made me wish I had waited before jumping into the book and training.

By 2016, I was getting bored with BPMN, and DMN, even with all its problems, was far more interesting. At bpmNEXT that year, Denis Gagne of Trisotech shocked me by demonstrating a browser-based tool that could model all of the diagrams and tables defined in the DMN spec using FEEL. I had known Denis for over a decade. In fact, he had wanted me to use his tool for BPMN Method and Style training, but I couldn’t because it did not have the style rule validation. But now he offered me a way out of the DMN corner I had painted myself into with Signavio, and we planned to work together on DMN training and possibly BPMN as well. Newly energized, I began to write a lot about DMN on my website and became a key evangelist for the new standard.

As a result, I was invited to deliver the keynote at a decision management conference in Stony Brook that summer. I used that speech to describe the transformative potential of DMN and to criticize the tool vendors who were claiming conformance without implementing its most important features, exhorting them to get going. In fact, I even tried to shame them into it by showing progress I had made myself implementing a DMN engine, although I am not a programmer.

I did it using XSLT, the only programming language I know, going back to my EFAST2 work. Apologies for getting a little geeky here, but programming languages are normally specified using a formal grammar that is processed by software to generate a compiler, and FEEL was no exception. I had no idea how to do that, so I did it the hard way by writing a string-matching FEEL parser/compiler in XSLT, using some advanced tricks I had learned doing the EFAST2 DER.[26] By the time of that keynote, my tool could execute many DMN models. In fact, since Trisotech had no DMN execution at that time, we were planning to offer mine inside the tool. At that conference I met Mark Proctor of Red Hat, developer of the world’s most popular business rule engine, called Drools. He told me he had assigned one of his developers, Edson Tirelli, to create a FEEL parser/compiler and DMN engine, and Edson said it would be done in two months. OK, game on!

[26] I forget the context, but at one DMN task force meeting, Gary Hallmark, the author of FEEL, commented, “Only a complete idiot would parse FEEL by string matching.” Guilty as charged.

I corresponded with Edson and he told me that my book had been very helpful to him in understanding DMN. Two months came and went, and my feeble string-matching parser could still do more than Edson’s. Around Christmas 2016, Edson caught up and immediately I capitulated. For one thing, Edson was a real programmer, in fact the smartest guy I had known since Bill Wray. For another, he worked for Red Hat, the number one rule engine vendor. And finally, Red Hat’s code was open source, meaning free. You can’t compete with that. Immediately I stopped work on my DMN execution code and used Edson’s, which was quickly incorporated in the Trisotech tool.

Edson’s DMN implementation was mostly complete by summer 2017. I created a whole new version of the DMN Method and Style training using Trisotech, breaking it into Basic and Advanced courses. I knew the market for DMN was smaller than for BPMN, but I’m sure I did not anticipate how much smaller. (A lot.)

One small bit of my code remained in the Trisotech tool. I used it to develop an analog to style rules called Decision Table Analysis, which would report any gaps or overlaps in the rules of a decision table, as well as violations of other best practices. No other DMN tool had it, but certain features added to DMN 1.2 were things my code could not handle, and I asked Red Hat to take over the Decision Table Analysis code, which they did.

The great thing about DMN is it allows non-programmers to create executable models. Even though DMN is nominally designed for business users, it requires some technical ability to fully exercise the power of FEEL. In 2018, Edson and I cowrote a new book, the DMN Cookbook, addressing a more technical audience, and later that year I wrote the second edition of DMN Method and Style, a huge improvement over the first edition. Sales of the DMN books and training started off slow, but they gradually got better.

Low-Code Business Automation

Training business users was my main business for the last decade, but I always enjoyed engagement consulting more. As the training slowed over the past year, I began to get a few engagements assisting clients with DMN. I always saw DMN’s real potential as the engine inside new cloud-native application software, and it’s starting to happen.

These engagements follow a common pattern. A subject matter expert has a great product idea but limited IT resources. He can demonstrate it with examples in Excel. My job is to generalize the business logic in DMN and replace Excel with a real database. DMN is important because the subject matter expert wants to understand the implementation himself, possibly even create or maintain it himself.

In practice, however, you need more than just DMN. You also need executable BPMN. With most tools this requires a Java programmer, but Trisotech did a brilliant thing, borrowing business-oriented elements of DMN, like FEEL, for use in BPMN. With that you can do true business automation without programming! It’s relatively new, but in these engagement projects I learned a number of tricks and techniques to make it work. This evolved into a methodology, and from that a new training course on Low-Code Business Automation with BPMN and DMN. Students could build a working Stock Trading App using real-time quotes from a third-party service, updating database tables, all without programming . Unfortunately, it never got much traction. The energy in Business Automation seemingly had moved on to the next new thing: Artificial Intelligence. But I no longer had the energy to move with it.

Retirement

Sales of the books and training declined significantly in 2023 and got worse in 2024. Junell was increasingly bugging me to retire. If I was going to have a business worth selling, I needed to do it soon.

Knowing I was considering retirement, Trisotech surprisingly wanted to purchase the business. Even though they never had any interest in training or professional services, they recognized that my style of business empowerment in automation – encapsulated in the Method and Style brand – was something they wanted to own. And so, in May 2024 they purchased all the Method and Style assets – the books, training, website, trademark, and IP.

As part of the purchase agreement, I would write one more book – now owned by Trisotech – on Low-Code Business Automation. To fit Trisotech’s new market positioning, it would be called Orchestrating Business Decisions Method and Style. (Hey, I didn’t choose the title.) I’m finishing that up now, and it should be out early in 2026.

In addition, with itp commerce’s acquisition by ELCA, I needed a new agreement replacing BPMessentials. We did an annual royalty agreement for 2024 and later completed a non-expiring fixed price agreement covering BPMN Method and Style training using ELCA’s tool, carved out from the Trisotech acquisition.

And that makes me now officially Retired.

* * *

It might seem that my so-called career progressed through a series of accidents. But in my view, each step followed naturally somehow from what came before. From photography to electronic imaging to document imaging to workflow to BPM consulting and training. Each phase carried over to the next.

Looking back, I feel I should have achieved more. Early on, I lacked self-confidence and was too risk averse. At MIT, I felt unprepared, at Polaroid, unqualified. I finally found my footing at Wang, at BIS was in full control, and after that I was on my way. Too old by then to really reach the heights, but I made a decent living and can’t complain. All in all, it was a good ride.

Epilogue: Whatever Happened with Wang and Polaroid?

Very few people who go off on their own stick with it as long as I did, 30 years. Working for large firms early in my career gave me valuable experience but also left me with a healthy skepticism about the competence at the top of once exceptional companies. So in researching this piece, I could not help a bit of curiosity about the fate of my former employers.

Wang

At Wang, Rick Miller eliminated the bank debt by the end of 1990 but could not return the company to profitability. He brought in consultant Ira Magaziner – better known as the architect of Bill Clinton’s failed health care initiative – who recommended Wang exit the hardware business altogether and focus on office automation and imaging software running on Unix. In exchange for an investment by IBM, Wang agreed to resell IBM hardware in 1991, but the company continued to lose money and filed for bankruptcy in 1992, emerging from bankruptcy in 1993 as Wang Global. The Wang Towers in Lowell, which cost $60 Million to build, were sold for $500K. The building was renovated and resold in 1998 for $100 Million.

Joe Tucci, once a BIS client of mine from Unisys, became CEO after Miller. He won a patent settlement with Microsoft in 1995, under which Wang received $90 Million and its image display software became included in Windows 95.[27] Tucci spun off the imaging software business to Kodak as Eastman Software in 1997 and sold the rest of the company to Getronics in 1999. Later, as CEO of EMC, it was Tucci who purchased Captiva and bought us that nice new kitchen in 2006.

[27] Microsoft’s Object Linking and Embedding (OLE), the successor to Windows DDE, infringed a patent from the long-gone Wang 42x project. Irony abounds.

Kodak, nearly as clueless in electronic imaging as Polaroid, could not make a go of Eastman Software. In a year or two they sold it to Sonny Oates, a notorious bottom-feeder who renamed it eiStream and mined the maintenance revenue. It was later rolled up with other first-generation imaging companies, including ViewStar, and renamed Global360, eventually acquired by Open Text.

There was no chance Wang could survive the change from proprietary hardware to standards-based “open systems” in the early 1990s. None of the minicomputer companies did. The people there were smart, innovative, and hardworking, but simply a victim of technological change. They did not deserve their fate.

Polaroid

I could not say the same for Polaroid after the departure of Land. The management there remained arrogant and obtuse in the face of an onslaught of electronic competition. Mac Booth, the plant manager who succeeded McCune as CEO, epitomizes the attitude:

The company is also betting that instant film, not a computer printer, is the best way to get high-quality prints from electronic cameras. Its scientists have developed a gallium arsenide chip that can convert the electronic information back into light rays that expose Polaroid Instant film. Anyone who says instant photography is dying has his head in the sand.

–Booth, quoted in Fortune, 1987, from Fall of an Icon: Polaroid after Edwin H. Land: An Insider’s View of the Once Great Company by Milton Dentch

They did have a project code-named Blink that used gallium arsenide LEDs to expose film as hard copy from electronic images. The problem then was there were no blue LEDs at that time; Blink would use special film in which an infrared LED would be processed as blue light. I don’t think they ever got it to work.

Also, according to Dentch,

Polaroid did establish a microelectronics lab (MEL) and hired, or attempted to hire, several industry experts. Though Polaroid was one of the first companies to develop a professional digital camera, it took so long perfecting the device that, by the time Polaroid introduced it in March 1996, the market was full of cheap competitors.

I sincerely doubt that a digital camera developed by Polaroid Engineering could be called “professional.” Polaroid had world-class optical engineers, mechanical engineers, and color chemists, but in electronics they were third-rate at best. The real problem was that the company just viewed cameras as a way to sell film. They could not see the point in a camera that didn’t use any.

Even in the area of hard copy, Polaroid failed to recognize the potential of materials other than photographic film. McCune actually bought an ink jet company, Advanced Color Technology (ACT), in the early 1980s, but Polaroid never developed it. Dentch again:

A cultural obstacle became a roadblock to success in this venture: our R&D team insisted ink-jet printing would never be as good as silver-halide imaging. As a result, research assigned low level engineers to work with ACT and never put significant resources behind the new company…. Our technical team, working with ACT, did develop novel inks which improved ink-jet quality as well as the hardware used to deliver the ink to the receiving paper. Ultimately, ACT was underfunded as the R&D team focus continued to be silver-halide films.

Booth was succeeded by Gary DiCamillo in 1995. He tried to rejuvenate the instant film business internationally, but revenue continued to decline, and Polaroid declared bankruptcy in 2001. In the reorganization, the company sold all its assets to One Equity Partners (OEP), a VC arm of Bank One, for $255 Million in cash and $200 Million in assumed liabilities, generally considered a suspicious fire sale. Compounding the issue were large retention payments to DiCamillo and a handful of other executives who had driven the company into bankruptcy. Previous executives saw their pensions reduced by 85%, as OEP had no obligation to keep funding the Polaroid pension plan.[28]

[28] I worked there nine years and received exactly zero in retirement benefits.

It gets even worse. OEP sold the company to Petters Group Worldwide for $426 Million in 2005, who was interested only in the Polaroid brand name, the real estate, and photography collection. Polaroid stopped producing cameras in 2007 and film in 2008. At the end of 2008, Polaroid filed for bankruptcy once again following the arrest of Tom Petters for running one of the biggest Ponzi schemes in history (second only to Bernie Madoff). In the final settlement, the Polaroid Collection – including works of Ansel Adams and others of that caliber – was auctioned off at Sotheby’s. Just so sad!

Following discontinuation of film production in 2008, a company called the Impossible Project was founded by former Polaroid employees in the Netherlands, who acquired the Dutch film factory along with the rights to produce instant film for vintage Polaroid cameras. However, the process had been lost and had to be rediscovered. After a period of development, the company began producing film under the Impossible Project brand in 2010, rebranded in 2017 as Polaroid Originals and then again in 2020 under the original name Polaroid. Against all odds, Polaroid today enjoys some success as a comeback story.