My So-Called Career/4

BIS Strategic Decisions

There are two kinds of industry analyst firms. One kind, like Gartner and Meta, sells to IT executives in end user organizations, who want to know where the technology is going and obtain third-party validation of technology decisions they have usually made already. The other kind, like IDC and Dataquest, sells to technology vendors. Those clients also want to know where the technology is going, along with help on competitive positioning of their products. In reality, they want to influence the analysts to say good things about their products. In addition, they want numbers: growth forecasts, market share, that kind of thing.

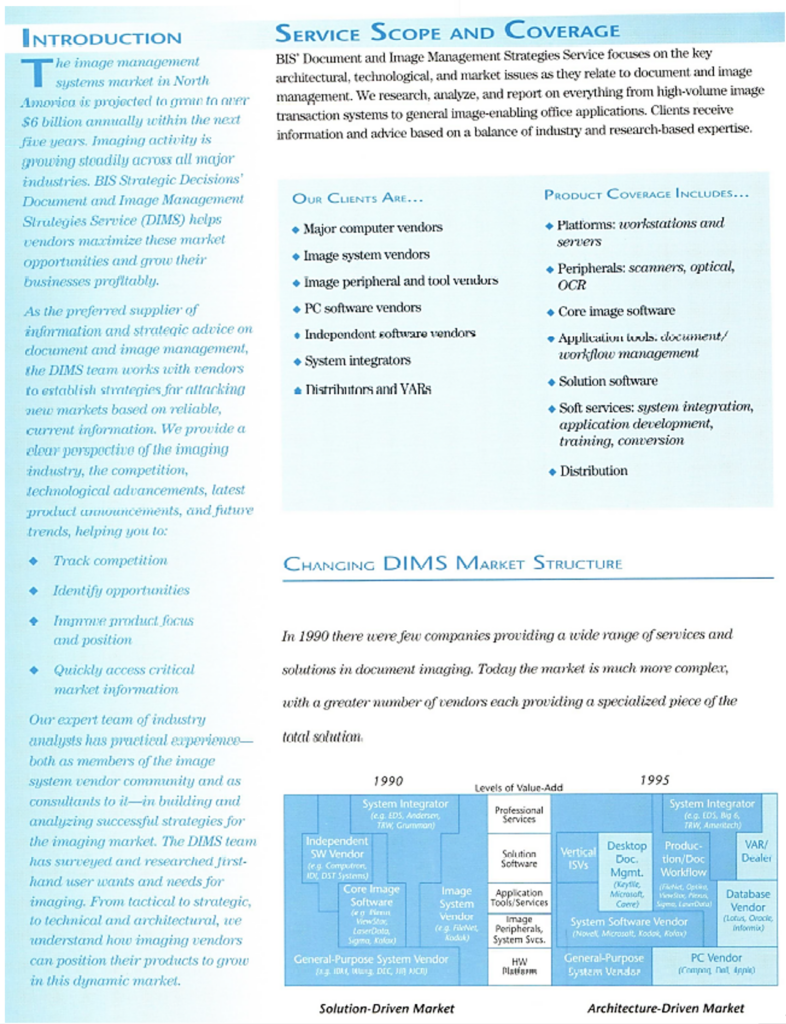

BIS Strategic Decisions was the second kind of firm. It was located in sleepy Norwell, MA, halfway to the Cape. The company started out as CAP International, CAP being Charles A Pesko. Charlie originally sold a single information service on office copiers (“Intelligent Copier-Printers”) and consumables, then expanded it into a news-and-numbers shop with services covering fax and other devices. Somewhere along the line, CAP International was acquired by a British company, BIS Group, who renamed it BIS Strategic Decisions. BIS in turn was owned by Nynex, the regional Bell operating company for the Northeast, today called Verizon. We had around 200 employees, and the Brits and Nynex generally left us alone.

The principal product at BIS was a set of subscription-based “continuous information services” (CIS). The company had some other product lines as well, including reports, conferences, and consulting, but CIS was the main one. For $15K/year per service, clients got regular printed news, analysis, and commentary, an annual forecast, and unlimited telephone inquiry. BIS had a successful document imaging service headed by Scot McCready, a brash young man with notoriously bad work habits. Suddenly they had a big hole to fill when Scot left to join arch-rival IDC in the spring of 1990. That was perfect timing, as I was hired to take his place.

I was recruited by Rai Wasner, senior VP in charge of the CIS business. My immediate manager, Roger Sullivan, was someone I knew, since he had been the WIIS marketing manager at Wang! Unlike all the other services at BIS, clients of my Document and Image Management Strategies (DIMS) service included both vendors and end users. Roger focused more on the end user business, where the company was a bit of a fish out of water. My focus was more on the vendor business, although I was actually responsible for the whole thing.

At this point I was 41. For my whole career, my job had been to implement requirements given to me. But this was different. At BIS my job was simply to grow the business, which when I started did $500K/year. When I left four years later, it was a $1.5 Million/year business, bigger and better known than Meta’s imaging service, or Gartner’s or IDC’s. I had a revenue quota every year – meet that or else! – but once I hit that, 10% of any incremental revenue was returned to me as bonus. Earlier in my career that would have been terrifying, but now I loved the financial incentive because I knew I could do this job.

I knew it because unlike most engineers, I paid close attention to competitive products. At both Wang and Polaroid, I would take a close look at them at trade shows and ask questions. I wanted our products to be the best in class, and I was interested in the technology. To be honest, in the industry analyst world the bar was set pretty low. Few analysts had any idea what they were talking about. They were English majors, for God’s sake. If they ever worked in the technology previously, it was as a marketing person or maybe tech support.

In terms of product and market knowledge, the other industry analysts could not compete with Roger Sullivan and me. We would tag-team on presentations. Roger was great at the high-level benefits and market trends. I was best at the technology behind the products. They called us “Fluff and Stuff.” Every imaging vendor became our client. We had a harder time selling to end user organizations, but we did get around 20 of those.

Roger did not help with putting out the service deliverables, the news, commentary, forecast, and telephone inquiry. Originally that was all done by me and one associate, Jane Stanhope. As the service grew, I added one more, Mary Bamford. Sometime after that, Jane left to join Scot McCready at IDC, so we were back to two, but together, Mary and I built a $1.5M information service. As an analyst, I became very well known in the industry and was often quoted in the trade press. People I never met knew my name and sought my good opinion. After Polaroid and Wang, it seemed very strange.

In those days, before the Internet, companies had no easy way of getting information about their products and strategies out to the public. There was a robust trade press, newspapers and magazines like Computerworld and Datamation, which were free to subscribers and contained lots of ads. They provided news but covered all of computing. The CIS filled the role of filtering and summarizing the news in a specific topic like document imaging and offering background info and expert commentary on top of that. When a new product release came out, vendors would have briefings just for the industry analysts, so we could provide more detail than you’d find in the trade press. That was easy money while it lasted; a few years later, free information on the Web would kill the easy part.

Getting our newsletter out in a timely manner became a sore point for me, because after we wrote it, the document would sit in the company’s desktop publishing queue for two weeks or more. They would use Adobe PageMaker to create layouts that were no better than what you could author directly in MS Word. I decided that in our service, we would adhere to a standard style guide in Word and skip desktop publishing altogether. That didn’t make me popular with some in the company, but we got our work out much faster (and it saved the company money).

Written commentary was my strongest suit. I don’t have a copy of it today, but I remember one of my first commentaries, maybe the actual first one, called “What It Takes to Compete,” meaning to succeed in the document imaging market. It’s something I had been thinking about for half a year as many new document imaging vendors were entering the field. The catalyst was Windows 3.0, released early in 1990 from Microsoft. Earlier versions of Windows were terrible. The WIIS workstation, you recall, had to create its own windowing environment. But Windows 3.0 was good and widely adopted. One of its key features was called Dynamic Data Exchange (DDE), which allowed an application in one window to communicate programmatically with another application in a second window, something needed in all imaging and workflow applications.[19]

[19] DDE actually started in Windows 2.0, but Windows 3.0 was the first version to gain wide user adoption.

Windows 3.0 triggered a whole new application architecture called client/server computing. Unlike the host-based architectures of IBM, DEC, and Wang, where the desktop is essentially a dumb terminal and all the processing is done on the host, client/server could take advantage of an intelligent Windows desktop (the client) that communicated to a backend server providing a shared file system, database, and peripherals. And not only was the client operating system – Windows – a standard supported by many vendors, but so was the server operating system, Unix. Where formerly Unix was used mainly in engineering workstations from companies like Sun and Apollo, now it began to dominate as a server operating system.

Prior to that, business software could run only on the hardware of a specific vendor. The business models of IBM, DEC, and Wang counted on that. Suddenly that was no longer true, and the combination of Microsoft Windows clients and Sun Unix servers quickly killed the Massachusetts Miracle. Minicomputers were dead and gone in a flash. It wasn’t just dopey Fred Wang. “Brilliant” Ken Olsen of DEC was forced to resign in 1992. Prime, Data General… who even knows those names today? The center of the computing universe moved in an instant from Route 128 Boston to Silicon Valley. What I wrote in 1990 was if your imaging product wasn’t based on Windows clients and Unix servers, forget it. And many of them were not, including those of new vendors just getting into the market. I was right about that, so it was a good beginning.

The AIIM Show was the big imaging industry event, and we put on a breakfast there for clients and prospects every year, very well attended and always a big hit. My part was highlighting the key events of the past year in a humorous way, a bit of “roasting” the vendors. IBM was the big dog in the industry and always an easy target. They had been long criticized for having two incompatible imaging products, one for the mainframe and another for their AS/400 minicomputer. Finally they introduced one on the modern client/server architecture and I announced that achievement by saying, “And now they have three incompatible imaging products.” Everyone thought that was hilarious, but later in the men’s room I was cornered by Mike Antonelli, their marketing VP and a former football player. I thought he was going to beat the crap out of me right there.

In my service I was essentially the product, but I also had to go on sales calls. On that front I had more interaction with Rai Wasner than with Roger. Rai was 5 or 10 years younger than me, but opinionated and cocky as hell. I had no idea how to do sales, and Rai teased me about that endlessly. His methods were strange but they seemed to work. He’d tell me, “Whatever questions they ask, answer No. No. No. Then Yes.” Stuff like that. I still don’t get sales, but I’ve gotten better at it.

One part of the job I did not care for was the annual forecast. We had to produce one, but we had no good methodology for doing it. To make it worse, Scot McCready’s last forecast, which I inherited, was way too high. And in a new technology business, the vendors – read, our clients – demanded good news, that is, continued growth. So we were kind of boxed in. Our forecasts remained high, too high. But no one cared.

There was a new imaging component company that was becoming very successful, Cornerstone Imaging. They made high resolution monitors for image display. Unlike Carlos Mainemer’s 200 dpi monitors at Wang, most image displays were lower resolution, and to fit a whole page on the screen the monitor controller had to omit some pixels, giving the image the “jaggies”. Cornerstone solved that problem with “scale-to-gray” built into the display controller board. To fit a page image on the screen it would average neighboring black and white pixels to gray. That sounds trivial but no one else was doing it, and it made Cornerstone successful. By 1993 they had a giant booth at the AIIM Show in New York and held a great party at Tavern on the Green. The following year, I did a special forecast for them of imaging displays that helped them with their IPO. That work later on led to good things for me.

BIS also had a consulting group that bid on custom projects. While small, they were run like a typical large consulting company, in that a senior guy – the “rainmaker” – would sell the project as if he would be working on it, but the work would actually be done by some clueless dudes right out of college. I still see it all the time: Accenture, Booz Allen, that’s what you’re going to get. One time, our service client NCR called with a special project, a detailed competitive analysis of imaging products. I knew we weren’t supposed to do special projects – our job was to put out the service – but it was for our client, with whom we had an established relationship. And we knew our consulting group had zero domain knowledge. They would surely mess it up, and we would probably lose NCR as a service client to boot.

I’m traveling, at an airport pay phone somewhere (no cell phones in those days), and Mary tells me NCR needs a quote right away. I knew it was something we’d have to squeeze in with our normal work, so I thought of a price that reflected that, even though it was probably too high for the client: $61K. Later I call her back. OK, she says, they accepted. Our consulting group was furious. That should be our project, they said. NCR would never hire you for that project, I answered. You know nothing about it.

But BIS said I had to give consulting a piece. We broke off something simple they could do with library research, but the consultant didn’t seem to be working on it at all. Getting near the deadline with nothing from him, I tried to track him down, but no luck. He didn’t even come into the office that much. So I fired him from the project, and we completed it ourselves. The client was very happy, and BIS got $61K in unplanned revenue with zero sales effort. Later that year, at performance review time I was sure to get a great one, since I had killed my number. But instead I got slapped down hard for taking that business away from the consulting group. On top of that, I had to forfeit 10% of the deal to consulting, who had done absolutely nothing on it! It was ridiculous. Roger had not defended me, and I never forgave him for that. Or the company; after I left, I felt fine about taking a bunch of clients with me.

One quarter, the CIS business overall at BIS missed their number. It must have been a bad miss because Rai was out, just like that. A year after that, Roger left to become marketing VP at a vendor company. I was made VP with another couple services in my P&L, but it was still basically Mary and I putting out the DIMS service. At some point in there we got the word “workflow” in the service name. Although it started as a benefit of imaging, workflow had become an important technology in its own right, with or without imaging. Rai had always hated workflow – too complicated, he said, just confuses the prospect. Same story as Wang. But now he was gone.

Relatively early in my tenure at BIS it came time to try to sell our service to Wang, where Horace Tsiang somehow was still Executive VP in charge of R&D. Wang was getting out of the VS minicomputer business, now selling its imaging software, called OPEN/image, on the preferred client/server architecture, Windows clients and Unix servers made by IBM. (That would have Dr Wang spinning in his grave.) I called on Horace in his penthouse office in the Wang Towers. All the time I had been at Wang, Horace had never asked my opinion about anything, but now as an outsider I was apparently a fountain of wisdom. I told him about something I had recently seen that Wang should be interested in, a company in New York, Sigma Imaging Systems, that designed workflows through diagrams. Today we would say, How else would you possibly do it? But prior to that, workflow – like that of FileNet – was defined using script programs not diagrams. We not only got the order from Horace, but Wang bought that company.

In addition to everything else, our service put on a conference every year for clients at a fancy resort hotel. It was a big money-maker, but it belonged to the conference group. It didn’t go on our P&L. That’s ok because putting on a conference is a huge amount of work. You have to know what you’re doing, and our conference group did. I show here the agenda for our 1994 conference, which by then was called the BIS Document Management and Workflow Conference. Note “imaging” was by then not even in the name.

The truth is that by 1994, I was becoming dissatisfied with BIS Strategic Decisions. Rai and Roger were gone. My service was successful, but the company was having hard times. It bothered me that I not only had to put out the service but go on every sales call. I was flying all over the country for this. The company had a highly compensated sales force, but as far as I could see they just wrote up the orders. They couldn’t close any business on their own. I felt I was towing the boat and it might feel good to just drop the rope.

At the same time, I don’t know what caused it but Nynex decided to sell the company to a multimedia investment firm, Friday Holdings, backed by Texas oilman Richard Rainwater and Hollywood moguls Barry Diller and Marvin Davis. Our business would be run by two newspaper executives from the Wall Street Journal, John Geddes and Norman Pearlstine. It did not look to be a win for the employees.

I’m not sure what Friday Holdings thought they were buying, but it didn’t take long for Geddes and Pearlstine to conclude that our company wasn’t that. Friday Holdings quickly bailed out, [20] selling the company to Gideon Gartner, who had sold Gartner Group years before and presumably had completed his noncompete period. The new company would be called Giga. It is now part of Forrester Research.

[20] Pearlstine joined Time Magazine as editor in chief; he later became editor of the LA Times. Geddes became managing editor of the New York Times.

In any event, I was out of there. I was going to drop the rope and do it on my own. In October 1994, I became Bruce Silver Associates, working out of the house in Weston. I was 45 years old.

Bruce Silver Associates

I called myself a consultant and independent industry analyst. As a consultant, I was more than a little apprehensive about asking clients for money when it was just me, unsupported by a corporate logo. Junell tried to convince me I could do it, and it turned out I could. As far as independent industry analyst goes, there was no such thing, but I did it anyway for about 15 years. I started making more money on my own than I had as an employee, enabling Junell to quit her tech job – she was then a product manager at DEC – and go back to school in psychology, in which she eventually got her PhD.

As a backstop, and because I didn’t want to leave BIS/Giga totally in the lurch, I contracted time back to them for the first 6 months or so. In addition, as I was thinking about leaving, I began work on a comprehensive report on workflow systems, which would be sold by the company’s report group under a revenue sharing agreement. This was a detailed review of 10 leading workflow automation products, comparing them in terms of platform support, scalability, flow mapping, runtime user interface, developer tools, work management, and exception handling. It was the only thing of its kind.

A key reason I thought going solo might work is I had a strong relationship with many of the key imaging and workflow vendors. I hoped to win retainer agreements with some of them that would include a mix of consulting days, speaking at events, and white papers. I did manage to take a number of clients with me on a retainer, and with others was able to do the same things on a one-off contract basis. I was the gig economy a couple decades before it became the norm.

I could write quickly, so white papers became a mainstay of the business. They placed the client’s offering in the proper business context and explained the significance of its features and capabilities. I offered the white papers in two forms, either bylined Industry Trend Reports or ghost-written, where my name did not appear. The price was the same, $15-20K for 3000 to 5000 words. For the bylined reports, I retained copyright and final edit, but the client had unlimited reproduction rights. Obviously, the client’s goal was to say great things about the product, but with the bylined reports, I had to tone it down, feel comfortable with what the report said. With the ghost-written, I just provided a draft, after which the client could modify it in any way they wanted. About 90% of the reports were bylined.

On the consulting side, I worked with both marketing and development on product positioning, strategic advice, and competitive analysis. My key advantage over my competitors was I spoke the languages of both marketing and engineering, something that was very rare.

I was still a well-known name in the industry and was asked by clients to speak at their conferences and customer events. The ones by Unisys in St Paul de Vence on the French Riviera were especially fun. I went there three times over the next decade, once with Junell. So much fun, we even put in a petanque court at our house in California!

Back then trade magazines were still common, and I picked up some easy money writing a column for some of them. One, Imaging World (later called KM World), paid $1500 for 300-500 words every month. I had lots of opinions and I could write very fast. The day of my deadline would arrive and I would knock one out in a couple hours. Unfortunately, the Web would kill that business. On the Web, information is free and everyone is a pundit.

Cornerstone to Captiva

Out of the blue, in 1995 the CEO of Cornerstone Imaging, Tom van Overbeek, invited me to consider joining the board of their company in San Jose. My BIS forecast of imaging displays had helped them with their investors, and now as a public company he wanted someone who knew the industry on the board. This was my first experience with that side of the Silicon Valley world, and it made a distinct impression. Tom was about my age, a hard-charging CEO straight out of the TV show Silicon Valley. In his spare time, he raced stock cars, so we met at Thunderhill Raceway in the Sacramento Valley. I flew to San Francisco and then a puddle-jumper to Chico, CA, where he picked me up. If there is a sport more expensive than racing horses, it must be racing cars. It’s very loud, also. At the end of the weekend he dropped me off at Amy and Eddie’s house on Sea View in Piedmont, which made an impression on him, too. Nothing impresses rich guys like even richer guys.

I must have done ok since he invited me to meet the other board members in San Jose. The other outside directors were all VCs and investment bankers, so it was a little intimidating. And then I was on the board. My first board meeting was a week-long retreat at the Ahwahnee in Yosemite Valley. (They weren’t all like that, unfortunately.) At that meeting all the talk was about Netscape, a new company that provided free software to access something called the World Wide Web. Little did anyone know how much that would change the tech world from top to bottom!

I would go to board meetings four times a year in San Jose. Our Weston friends and neighbors John and Betty Weis had just moved there, so I always had a nice place to stay. In return I was able to get their son a job at Cornerstone. I was traveling to Silicon Valley a lot at that time, and in 1996 Junell and I planned to move to the Bay Area ourselves, but, as in 1982, we were stymied by the home prices. Tom suggested we look in Santa Cruz. We had lunch at Zelda’s on the beach in Capitola while we perused the real estate brochures. It reminded me of a Caribbean vacation, and we moved to Aptos the following year. That house was a story in itself. I even made a book about it.

At first, Cornerstone’s monitor business was doing great, but like everything else in tech, as the baseline PC technology gets faster and faster, eventually you don’t need specialized hardware to do the job. As the stock price went lower, Tom wanted to buy back stock to prop it up. I was the only director to vote against it, and when they asked me why, I said “You might find you need the money.” That turned out to be the case.

Cornerstone had acquired a second line of business, a software company called Pixel Translations. Pixel was headed by Steve Francis, the OCR guy from Palantir/Calera I’d worked with at Wang. They had created a standard for high-speed scanner drivers called ISIS and successfully licensed it to just about every scanner manufacturer. This software business was smaller than the monitor hardware business, but it had higher margins and unlike monitors, it was growing.

In addition to the ISIS drivers, Pixel’s key product was Input Accel, an automated workflow system for scanning and document capture. It was the first product of that kind, and it did very well. At Cornerstone, the Pixel business was run by Kim Hawley, a young woman who had been head of marketing. To make a long story short, around 1996 Tom and Kim had an affair. I forget the exact sequence of events, but soon Tom left Cornerstone, Pixel became the main business, and the company name was changed to Input Software, with Kim as CEO.[21]

[21] Tom and Kim left their spouses and got married. We socialized with them a bit, but Tom’s right-wing politics was a barrier. Tom and Kim are still married today.

Now I’m going to skip ahead to finish this particular story. In the late 1990s, the Web sucked all the oxygen out of the tech world. It was the dot-com era, and investor interest in archaic things like document imaging declined precipitously. In customer organizations, it was just “the scanner in the basement,” not something strategic. Even though Input Accel was doing well, the stock kept going down, so I guess not that well. We tried changing the focus to something more “webby,” even changed the company name to ActionPoint.

The dot-com boom popped in 2000, and after that all tech stocks went down hard. It turned out we did need that cash after all. Around 2001, ActionPoint was forced to merge with another image and data capture company, Captiva Software of San Diego. It was nominally a merger of equals. Kim would be CEO but Captiva would have one more board seat and the headquarters would be in San Diego. The directors from ActionPoint would be Kim, Steve Francis, and – for some unexplainable reason – me. I kept thinking of that 1960s cult movie Putney Swope, about an ad agency where the CEO suddenly dies and the board must immediately have a secret ballot to determine the new CEO, with the proviso they cannot vote for themselves. So they all vote for the one they think no one else will vote for, the black guy. I must have been the black guy.

Kim was CEO for a year, then Steve was CEO for a year, and then Reynolds Bish, who headed the old Captiva, became CEO. Reynolds was an accountant by training, a bit of a cold fish, but a much better CEO than we had had previously. It was more of a real board of directors, too. I was on the Nominations and Governance Committee, which sets the policies for the board, and the Audit Committee, which oversees the annual audit. The latter was a lot of work because of the new Sarbanes-Oxley law, passed in the wake of the Enron scandal. Companies even as small as Captiva had to formally document procedures for revenue recognition and all kinds of financial reporting. But it was great experience, and I wound up writing a number of white papers for clients about Sarbanes-Oxley reporting.

Reynolds did a great job of growing the business, and in December 2005 we sold the company to EMC. We had a blowout celebration at Torrey Pines Lodge in La Jolla and all directors got a Rolex watch (I gave mine to Aaron.) With the profit from my options, Junell and I built the world’s fanciest kitchen in our Aptos house.

Document Management

The vendor consulting business only works when the technology is just getting going, in the “early adopter” phase. Once it matures, end user organizations may need help, but not the vendors. By around 1995, imaging was reaching this point. Until then, the terms document management and imaging meant pretty much the same thing, but now there were revisable word processing documents – contracts, standard operating procedures, new drug applications – that needed management software. This was a new discipline and I didn’t know much about it. I thought about partnering with another analyst in that field, but FileNet bailed me out by buying a revisable document management company. They coined the term “enterprise content management” to mean a unified platform for handling images, revisable documents, and computer-generated output. Other imaging companies followed suit, and since I already had relationships with many of them, my consulting and white paper business expanded into all parts of enterprise content management, which grew to include web content, email archives, and retention management as well.

BPM

Soon I began to hear buzz about something called business process management (BPM). It sounded like workflow, but the leading vendors were companies I never heard of. The technology was totally new to me, as well. I understood that as a serious threat to my business, so I dedicated a few months to learning all about it. On the technology side, it included workflow, which came to mean automating the flow of human activities in a business process, but it also included enterprise application integration (EAI), a topic about which I knew nothing. And there was also a management discipline of BPM that had nothing to do with technology but was about business process improvement. These three components – workflow, EAI, and process improvement – made BPM a confusing hodgepodge that would become the central focus of my business for the next 15 years.

The new energy in BPM seemed to be coming from the EAI side. Recall I earlier mentioned DDE in Windows 3.0, a form of application integration using remote procedure calls (RPC) within the Windows desktop environment. At the enterprise level, there had been similar RPC technology as well, point-to-point connections between a business application and various other systems and databases in the company. As this integration architecture became increasingly unmanageable, EAI had come to mean a common message bus that linked all enterprise systems. Instead of a separate point-to-point connection between every pair of systems, each system just had to communicate with the bus.

Now message bus vendors began to automate sequences of integration steps to form a straight-through process and called it BPM. That was new and interesting to me. Some of them tried to tie in human activities as well. After a ton of library research, I began to call on these vendors – I was an independent industry analyst, after all. I didn’t know much about the topic, but that was ok, they were happy to educate me. Remember I said the bar for industry analysts was pretty low. I got some white paper business out of it.

Around 2002-2003, a new technology called web services came on the scene and shook things up some more. In the dotcom era of the late 1990s, the Web was simply a way to advertise your business, maybe with some rudimentary e-commerce. But it came to have a transformative effect on the entire world of technology. One effect was standards. Before the Web we had almost no technology standards that were universally supported. Sure, Windows and Unix were widely adopted operating systems, but they were not universal. The Web changed all that. The language of a web page, called HTML, was a universal standard. In addition to Netscape, which became Firefox, we had Internet Explorer, Chrome, and a bunch of other web browsers that all supported that standard. Web services was the idea of applying the technology and universal standards of the Web to EAI. Instead of RPC that was language-and system-dependent, applications would describe their callable interfaces using standard Web protocols and a standard language, XML, like HTML just tagged text and universally understandable.

In 2003 I came across a startup called Intalio that was trying to use web services to create a standard process automation language. It was run by twenty-something immigrant from France named Ismael Ghalimi. Ismael was a brilliant guy. We hit it off from the start, and he had a strong influence on the next phase of my career. Intalio’s language was called BPML, the Business Process Modeling Language. Each step, or activity, in the process was a web service. At each step, the process engine would issue its RPC call by sending an XML message, and the service would return an XML response message. Human tasks would be modeled as web services as well, although this was not proven to work very well. In principle, then, BPML would automate an end-to-end business process containing a mix of machine and human activities through XML messages. The messages could be sent either via a message bus or using the standard protocol of the Web, called http. It sounds simple, but this had not been tried before.

Moreover, BPML would be created not by writing programs but graphically, in diagrams, using a standard notation called BPMN, or Business Process Modeling Notation. The intent was that business people, not programmers, should be defining the process logic that runs their business. That part was revolutionary. A book called BPM: The Third Wave by Peter Fingar and Howard Smith evangelized the idea and caused a sensation in 2003. Conceptually, BPML and BPMN solved a lot of problems, and many software vendors were interested in them.

A consortium of 200 vendors called BPMI.org was formed to shape BPML and BPMN into useful standards. There was just one problem: The core standard defining the interface of a web service, called WSDL, was not finished, and when it came out it was not compatible with BPML. IBM and Microsoft came out instead with their own web service orchestration language called BPEL, Business Process Execution Language. It worked with WSDL. In an instant, those two companies obsoleted BPML, the work of 200 companies. That’s the way it goes sometimes.

While BPML was dead, its graphical notation BPMN was not. It looked like the swimlane flowcharts that the process improvement guys – the third leg of the BPM stool – had been using for years. They used process diagrams not to automate the process but simply to describe it: for documentation, analysis, and process improvement. Unlike the automation vendors, they had no interest in BPEL.

The automation vendors needed a standard like BPMN to get business people interested in the new web services style of EAI called service oriented architecture (SOA). In fact, some of them created free BPMN tools as a way to market their process automation software. That went a long way toward popularizing BPMN, even though most users just wanted it for process documentation and analysis not automation.

Ismael Ghalimi was the one that urged me to start my own website covering BPM. My only competition was Sandy Kemsley, a blogger in Toronto. Blogging software now made it simple for non-programmers like me to publish news and commentary on a topic, to create name recognition and a following. I also published my white papers there. Since my beat was covering the emerging landscape of BPMS (BPM Suite) vendors, I called the site BPMS Watch. As my fame from BIS days wore off, the website gave me a renewed following and name recognition. Sandy and I are still friends.

All this created great ferment in the BPM world and lots of new vendors, all of which was great for my business, both on the consulting and white paper sides. In addition, having done all this background research, I wrote up and sold a series of reports on BPM Suites (BPMS). There was a big report on the system technology, and individual reports on BPM vendors. The whole set cost several hundred dollars. When I got an order, I would have it printed at Kinkos and mail it out. I also charged the vendors to participate in the individual reports. Even though I worked out of my house in the total boondocks of Aptos, vendors would make the trek there to brief me. All in all, in the mid-2000s my business was very good.

EFAST

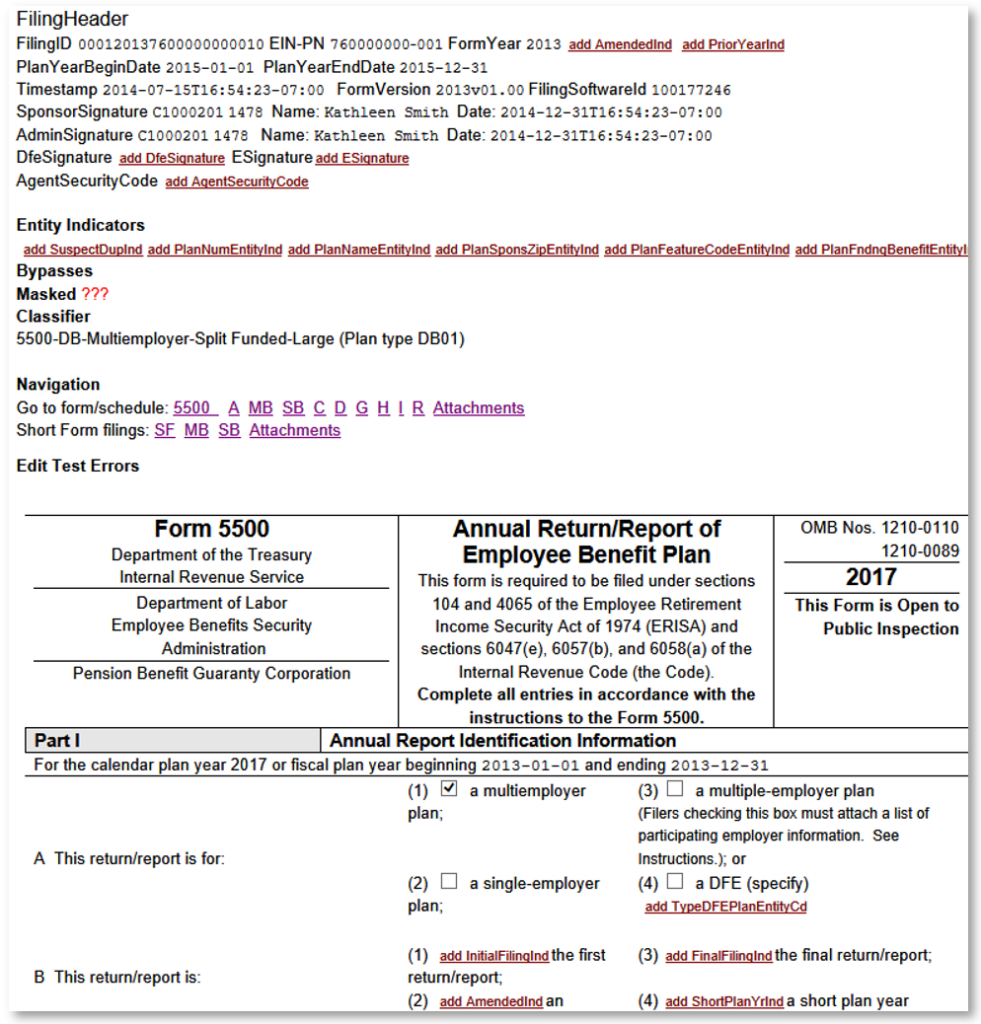

After I left BIS, I did some contract work for Rai Wasner, who had set up his own business called Rheinner Consulting. He subbed to me part of one project I continued to work on until 2021. It was called EFAST, processing the 5500 series filings for the US Dept of Labor (DOL). These are annual reports submitted by every employer detailing the status and financial condition of its pension, 401K, and employee health plans. Back then that was 1.2 Million annual filings, totaling 25 Million pages, for sure more than that today. Previously the data had been captured by the IRS, keying from paper with microfilm archiving. Now the IRS was handing it over to DOL, who put out a Request for Proposal (RFP) in 1997. DOL’s contractor for technical support on the procurement was Mathematica Policy Research (MPR) in Washington. They subbed out the technical advisory piece to Rheinner, who subbed out part to me. My job was, along with Rai, to spend a week or more in Washington DC reviewing the bids.

The RFP required scanning with image and data capture using OCR and key-from-image data repair, which explains my involvement. In the end there were only two bidders, NCS and the Federal division of Wang.[22] We wrote up detailed comments on each bid. From a technical standpoint, the NCS proposal was decidedly better. I believe the costs were about the same. But the DOL Procurement shop was so afraid of a protest that they awarded the Year 1 cost-plus design phase to both bidders. What wimps! Cost-plus means the vendor is paid for all development costs plus a modest fee. Yes, taxpayers, this is your Federal government in action, absolutely disgusting.

[22] Technically one could argue I had conflicts with both. Wang was my former employer, although they were bidding OPEN/image not WIIS, and NCS’s proposal included InputAccel from Input Software, where I was on the board. But no one objected.

At the end of the development period, each vendor had to provide a live demo of their system. We provided test filings of various types and determined the accuracy of the captured data. In the end, NCS was awarded the contract, with production to begin in early 2000 at their facility in Lawrence KS. Before then, there was additional development work required by Northrop Grumman, NCS’s design partner in the DC area. Certain functions were missing in the software, and I was trying to talk to the Grumman engineers about the technical issues. Some DOL people were afraid that any direct questioning of Grumman would cause NCS to sue the government for extra money, claiming a change in the requirements. In fact, a junior MPR guy threatened to fire me if I even talked to Grumman about the issues. But that was stupid. I talked to the Grumman technical guys and we worked it out. It was that junior MPR guy who eventually got fired.

By this time, I was doing all the Rheinner work on EFAST. Rai was billing MPR, taking a cut for himself and then paying me. Meanwhile, I had moved from Weston MA to Aptos CA. Soon Rheinner ran into some cash flow problems and stopped paying my invoices, but I was well known enough to MPR by then to cut Rheinner out of the picture and have them contract directly with me.

Most of the 5500 series filings were filled out using DOL-approved software, the pension equivalent of TurboTax. That was a big help because the software could encode the entered data in a 2-dimensional barcode in the printed output. When the filings were scanned, the 2D barcodes could be read from the image with 100% accuracy. A fraction of the filings were filled out manually, either typed or handprint. For those, the OCR accuracy was not great, but the system could flag low-confidence fields for key-from-image data repair.

The facility in Lawrence was a huge warehouse-like structure filled with paper handling equipment, high-speed scanners, and computers for data repair and analysis. Every day they had to slit the envelopes, count the pages, batch filings with hand-marked separator sheets, all sorts of things like that. From scanning to data repair the workflow was automated by InputAccel. At the end the data and images had to be formatted for transmission to the Federal agencies.

In production, things went much slower than planned. The data delivery was always late and there were massive backlogs. That was good for me, because I began to use a simulation tool called ProModel to reverse-engineer the queues at each step from the reports of completed filings. That generated lots of billable hours for me, although it didn’t make things go any faster in Lawrence.

Toward the second half of the 10-year EFAST contract period, the sources of the problems were clear: paper and people, too much of both. The new EFAST2 system, to start in plan year 2009, would eliminate both of those things. It would be 100% electronic data submission using web services – no paper, no people (except for call center support). Today such a design might not seem unusual, but back then it was unheard of, especially from DOL, the most tech-unsavvy department of the US government! What about the filers who didn’t use filing software? The little old lady who has a self-employed 401K? For them we created a simple web application called IFILE. If the little old lady doesn’t have a computer, she could use one in the local library. There would be zero paper filings. I still can’t believe we got them to go that far.

This time I had a major role in writing the technical requirements for the RFP, as well as in later specifying the Data Element Requirements, or DER. Since we were using web services, the data elements were specified using XML, as were the web services themselves. When we started planning EFAST2, I didn’t know anything about XML or its data definition language XSD or its mapping language XSLT. During that time, we visited an IRS facility where they were starting to implement eFile for the 1040 forms. I saw their developers were all using a tool called XMLSpy from Altova to work with the XML data. On returning home, I got that software, used it to learn all about XSD and XSLT, and have used it in much of my work (not just EFAST2) ever since.

By the time we put together the DER, I was fully XML-savvy. I developed XSLT programs to automate the assembly of the DER, which is over 1000 pages of data element requirements that are updated every year. Not only that, I used another Altova tool called Stylevision to create editable XML forms formatted to look like the printed EFAST2 forms, that validate the entered data against both the rules of the XSD and about 300 edit test rules implemented in XSLT. These rules are used by MPR to check the edit tests and annual form changes. Those rules are the same as the ones implemented by EFAST2 in production. They have to be, since we define them for the contractor. In fact, when a filer submits the filing, the system checks it against those rules in real time and returns a list of errors, if any. In that case the filer must fix and resubmit.

The result from the start was 100% clean data delivered right away to the government agencies. EFAST2 has been running for over 10 years now and is a fantastic success. My work on it toward the end of my involvement was just 15-20 hours a year updating the DER and the testing tool with annual changes in the data and edit tests.