My So-Called Career/3

Wang

Have you ever heard of the Massachusetts Miracle? It made Michael Dukakis the Democratic nominee for president in 1988. By the early 1980s, computer companies in the once down-and-out mill towns north and west of Boston had made Massachusetts the high-tech capital of the world. We had Digital Equipment Corp (DEC), Data General, Prime, Apollo, Computervision… and Wang Labs, where I found work after leaving Polaroid.

Like Polaroid, Wang Labs was run by its founder, an entrepreneurial inventor named An Wang. Like Polaroid, the company had recently enjoyed years of spectacular growth. And like Polaroid, it was heading for an equally spectacular fall. But nobody knew that last part yet.

An Wang

An Wang came to the US from China in his teens in the 1920s. In the earliest days of the computer, he studied engineering at Harvard, where eventually he got a doctorate. Back then, computer memory was made from electromagnetic cores, and Wang wound them by hand. While at Harvard he worked at a company making core memory when he figured out a better way to read out the data. He patented the idea himself, which made his employer very angry. Several years later, he licensed that patent to IBM for half a million dollars, enough to fund his new business. But Wang always felt that IBM had cheated him, and he held a lifelong grudge against the computing giant.

Like Land, Dr Wang was a creative genius. He developed LOCI, the first electronic calculator that could compute logarithms. When its results disagreed with published loan amortization tables, it was his machine not the tables that was correct. It was a bulky device, soon replaced by a much smaller one, the 300. Its main customers were automobile dealers who suddenly were required to disclose loan details like annual percentage rate to their customers. Wang’s calculators were built from individual transistors, and when he saw integrated circuit vendors like TI getting into the business he quickly got out. Quite a difference from Polaroid right there!

He also built small computers. Unlike the big mainframes from IBM, which were designed for batch operation, the new so-called minicomputers were designed for users at terminals to interact with the computer in real time. While the other minicomputer companies like DEC and Data General focused on number crunching, Wang invented the technology of word processing, in which a whole document could be edited in the computer and then printed out – initially on an IBM Selectric typewriter. Today we take word processing for granted, but all through my days at Princeton, MIT, and Polaroid (until Engineering), we just had typewriters and lots of White-Out to correct mistakes, no word processing.

By the late 1970s, IBM and DEC had word processing, too, but Wang had a key advantage. Where those companies used “dumb” terminals – basically just a keyboard and display – Wang’s Office Information System (OIS) put a microprocessor in its terminals, so the intelligence to do word processing was actually at the desktop. This innovation of OIS was developed by Don Dunning, who was to be my manager.

Wang’s flagship product line was the VS, a powerful minicomputer. By the early 1980s, minicomputers like the VS and DEC VAX began to challenge IBM mainframes. In computing, this was where the real action was. If you want an idea of the intensity of that period, read The Soul of a New Machine by Tracy Kidder, maybe the best book on the history of computing ever. It describes the race between Data General’s Eagle and Digital’s VAX for supremacy in 32-bit minicomputers. Wang’s VS didn’t try to compete on number-crunching power. Its focus remained on office automation.

The OIS and word processing made Wang Labs a very successful company. While Dr Wang ran R&D, operations was run by John Cunningham, a working-class Boston Irish type. Cunningham had worked his way up from a lowly salesman in the Chicago office to run sales, marketing, investor relations, whatever was needed. He was the only one who could push back on Dr Wang. Everyone loved John Cunningham, and after he rose to be COO he fully expected to succeed Dr Wang as CEO someday.

But Dr Wang had other ideas. Even when the company reached $3 Billion, he saw it as a family business. He wanted his name to stay on the building. As the company expanded, he raised money through debt rather than equity because he did not want to dilute the stock, which he wanted his family to control.[15] Most significantly, he wanted his son Fred to succeed him as CEO.

[15] To do this, he created separate classes of stock, one for the public and another for his family only. This violated the rules of the New York Stock Exchange, and Wang stock had to trade on the lowly American exchange as a consequence.

In 1980, Dr Wang shocked the company by naming Fred, just a few years out of college, to succeed him as head of R&D. Things went haywire quickly, as disputes among rival managers formerly resolved by Dr Wang just festered unresolved by Fred’s “collaborative” approach. All commentators blame the downfall of Wang Labs on Fred, who clearly was not equipped to run it. That is undoubtedly part of it, but not the whole story.

PIC/Personal Filing System

My own story in a sense begins on October 4, 1983, a year and a half before I joined Wang Labs. On this date Wang announced a series of truly bold, innovative products that would be released in the following six months. It was Fred’s coming out party as head of R&D. The problem was none of these products existed, some not even on paper. They were pure vaporware.

One of those products was the Professional Image Computer, or PIC. It was a special version of the Wang PC that supported storage and retrieval of paper documents in the form of scanned electronic images. By that time, Wang had a PC that ran on MS-DOS but it was not hardware-compatible with the IBM PC and its many “clones”. Before the IBM PC, all computers were proprietary, incompatible in both hardware and software with those made by other vendors. Wang and the other minicomputer vendors liked it that way, even with their own PCs.

In the spring of 1985, I was hired by Wang Labs to work on the PIC project. PIC was headed by Stan Fry, just a few years older than I. Stan was “Fred’s guy” at a time when few other R&D executives would make that claim. PIC was kind of a matrix organization, not part of the regular org chart. There was a talented team of hardware engineers under SK Ho, an imaging software group under Nancy Webb, and database people under Murray Edelberg. The PIC product manager was Thom Tillis, now a Trumpish senator from North Carolina. It was an interesting and talented crew.

Officially I worked for Don Dunning, the man who put the Z80 microprocessor in OIS, now a VP in charge of Wang peripherals – printers, disk drives, monitors, etc. I don’t remember my interview with Stan but I do remember the one with Don, because to his detailed questions about my work at Polaroid I had to answer, “I can’t tell you that, it’s proprietary.” It was the truth – Polaroid was maniacal about secrecy – but I’m sure I sounded like a Trump official in front of the judiciary committee. Don just about threw his hands up in the air, but apparently the fix was in, since I got the job. It must have been the words “electronic imaging” on my resume. There weren’t many people with that at the time, and it was go time for the PIC.

On my very first day at Wang, Stan brought me up to Dr Wang’s office in the Penthouse of the Wang Towers. Ed Lesnick, Dr Wang’s executive assistant, had a project for me, personally. Uh oh. This was my first day. Dr Wang wanted to be able to take reports and articles that he read and mark certain words or phrases in yellow highlighter. Then he wanted to scan those on the PIC and be able to retrieve them by searching on the highlighted words. That was Day One.

On Day Two, Stan and I took a trip to Kurzweil Computer Products in Cambridge, close by MIT and Polaroid. Ray Kurzweil is another one of those polymath scientist/inventors like Land and Dr Wang. Inc. magazine ranked him #8 among the “most fascinating” entrepreneurs in the United States and called him “Edison’s rightful heir”. He later wrote books like The Age of Spiritual Machines and The Singularity Is Near. He gives TED Talks. That kind of guy. Back then, though, his claim to fame was a reading machine for the blind using optical character recognition (OCR) technology. Our interest in Kurzweil was OCR.

When you scan a paper document, a person can read the displayed image, but a computer cannot understand what it says. It’s just a picture of the text, not actual text. OCR tries to convert that picture into the text. Prior to that time, OCR worked only with specific fonts, and in the age of typewriters this was often OK. But word processing spurred the development of laser printers supporting a wide range of fonts, for which traditional OCR technology was useless. You needed new “omnifont” OCR like Kurzweil’s to handle it. You can see why this was a critical technology for Dr Wang’s Personal Filing System.

Recently I did some research on the origins of document imaging at Wang. It started around 1981-82 out of a visionary Wang project called Advanced System Architecture (ASA), a reaction to the Xerox Star workstation. Engineers at Xerox Palo Alto Research Center (PARC) in 1980 had created in Star the basic user interaction paradigm we still have in personal computers today: the graphical user interface with multiple application windows, icons, mouse, etc. It was the forerunner of the Apple Lisa, then Macintosh, and later Microsoft Windows. Wang’s ASA basically tried to implement those ideas with some extra features, one of which, the Camera Option, became the PIC. Vincent Flanders in 1986 recounted the fate of ASA:

By the time I joined Wang, however, the Camera Option had been revived as PIC, an imaging version of the Wang PC, and the ASA workstation architecture had also been revived under the name OA-32, later called 42x. It was basically the Apple Mac as a Wang product.

The reason I mention this background is I also recently discovered my notes from March-April 1985, shortly after joining Wang, concerning Dr Wang’s Personal Filing System, renamed the Departmental Filing System.[16] It was to be implemented as an OA-32 application, not part of PIC.

[16] The only reason I have retained those documents is they were subpoenaed by FileNet in a patent suit brought by Wang in 1995. Most papers from those early days at Wang were thrown out long ago.

Meanwhile the PIC concept was evolving. The PIC scanner, which predated my arrival, looked like a photographic copy stand, not too different from my Polaroid slide printer of 1977. It was suitable for imaging one page at a time, very slowly, nothing practical for business. The application of document imaging that customers seemed to want was a Records Management System (RMS), providing the ability to retrieve a document image from thousands or maybe millions on file and display it on the screen. For that purpose, the PIC RMS project would integrate special micrographics “jukeboxes”, one from Ragen Instruments using special roll microfilm cassettes ($150K/1.2M pages) and one from Tera Corporation using specially notched microfiche ($20K/250K pages). Given the address of a page on a particular cassette or fiche, those jukeboxes would robotically retrieve the cassette or fiche, scan the microscopic page, and deliver the image data to the PIC workstation. We weren’t storing the image data, just retrieving and displaying it on the desktop.

The problem with storing document images, as it had been for electronic photographs at Polaroid, is they contain a lot of data, so mass storage on regular hard drives was very expensive. Document scanning typically captured just one bit per pixel, but at the minimum legible resolution of 200 pixels/inch, that comes to around 4 Megabits per page, or 500KB. The data is typically compressed around 7:1 using an algorithm developed for fax machines, so that’s 70KB per page compressed. In 1985, a 30MB hard drive costing $3K could hold around 400-450 compressed pages, so storing tens of thousands of pages on magnetic disk was not practical. If you wanted to store and retrieve the kind of page volumes used in records management, in those days you needed an optical disk jukebox such as the one created by FileNet ($180K/1M pages, plus the cost of the drives and media). Wang did not have optical disks in mind at that time.

So Wang at that time was working on document imaging at three levels: a feature of a personal Folder app on OA-32; a Departmental Filing System (DFS); and a large Records Management System (RMS). Key DFS components were the Smart Scanner per Ed Lesnick’s wish list, OCR, optical disk storage, and an image-capable laser printer. Retrieval would use the RMS software as much as possible.

But as you might guess from the ASA project, management upheavals would upset those plans. In the summer of 1985, Fred Wang took over manufacturing, a clear signal he would become CEO. At that point John Cunningham resigned and R&D had a new executive, Horace Tsiang. Horace was a VS guy. He was interested in RMS, but as a mainstream VS-based product not as part of PIC or OA-32.

Phase II RMS

When Horace came in, suddenly Stan Fry was gone. Thom Tillis was gone. For some reason, I was not gone. In fact, I inherited SK Ho’s imaging hardware engineers, and moved down to the 4th floor next to Don Dunning’s office. I was no longer working on pie-in-the-sky “advanced research” programs like OA-32. We had a mainstream Wang product to get out the door, and all the imaging hardware was now my responsibility.

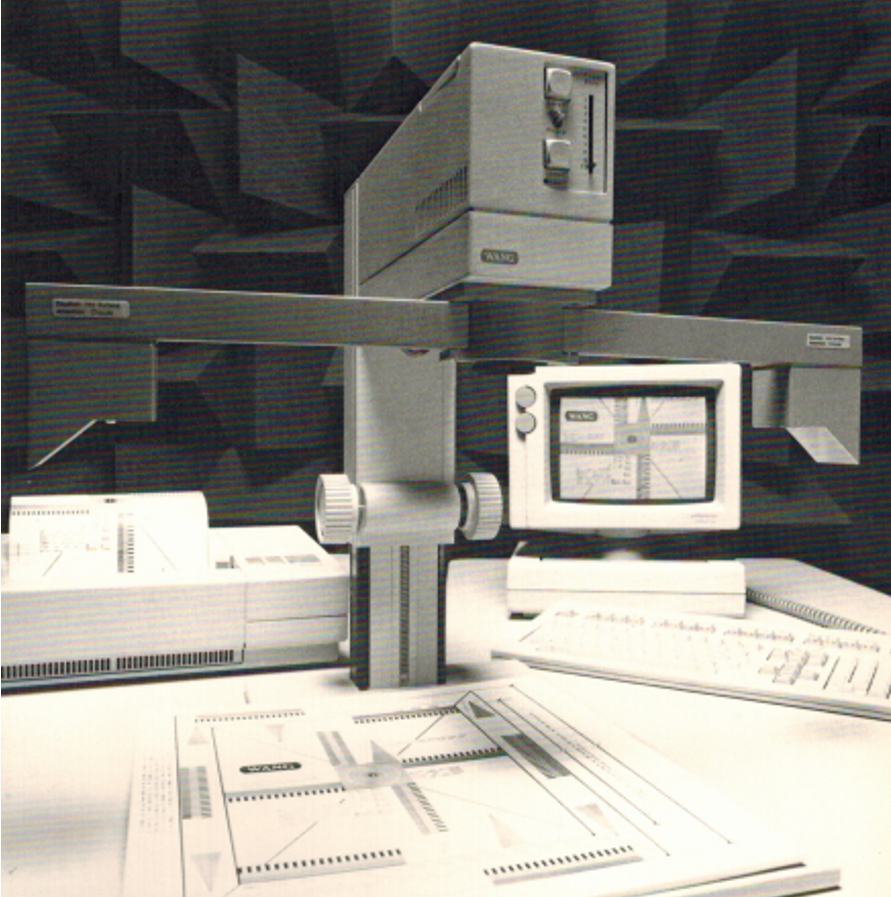

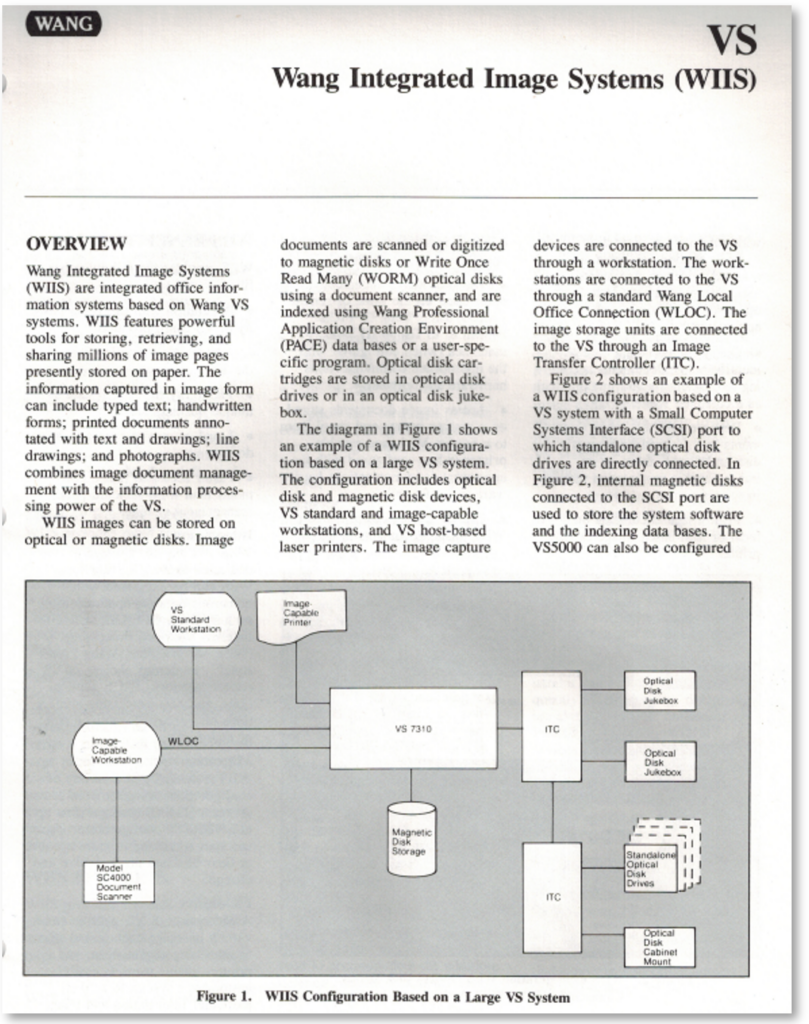

The new “Phase II” VS-based RMS program kicked off in August 1985. The proposed configuration is shown below.

As you see, the image storage was still microfilm and microfiche, connected to the VS by an Image Transfer Controller (ITC), designed by Bill Agudelo, now one of my engineers. The image workstation was still the PIC, containing new boards for image decompression and hi res display designed by Carlos Mainemer, another one of my engineers. These guys, whom SK had hired, were brilliant engineers. Polaroid had no one like them, trust me. I don’t know what SK had done to cross Horace, but all of a sudden they worked for me.

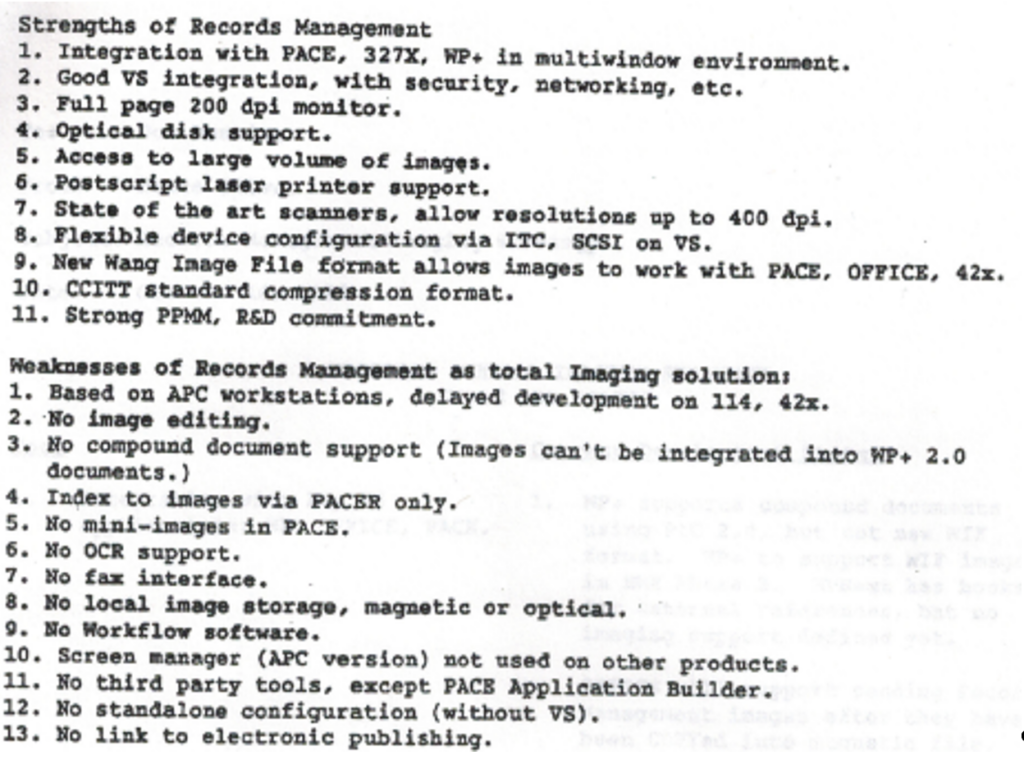

It didn’t take long to conclude that microfilm was the wrong way to go for RMS. A trip to the AIIM show in San Francisco confirmed this. AIIM had always been a micrographics-oriented show but now it was all about digital imaging, and other companies getting into it were focused on digital image storage using optical disks. I believed what we were working on was better than the competition, but we needed to add optical disk storage.

At that point I had a lot on my plate. I was responsible for all the hardware for the imaging workstations and VS-connected peripherals, now including optical disk drives and jukeboxes. I was also responsible for sourcing a new document scanner suitable for high-volume image capture, customizing it to our needs, and creating the scanner controller hardware and firmware. In addition, I had to come up with fax and OCR capability, hardware and software. My group, which had about 10 hardware engineers to start, grew to around 30, hardware and software, over the next two years.

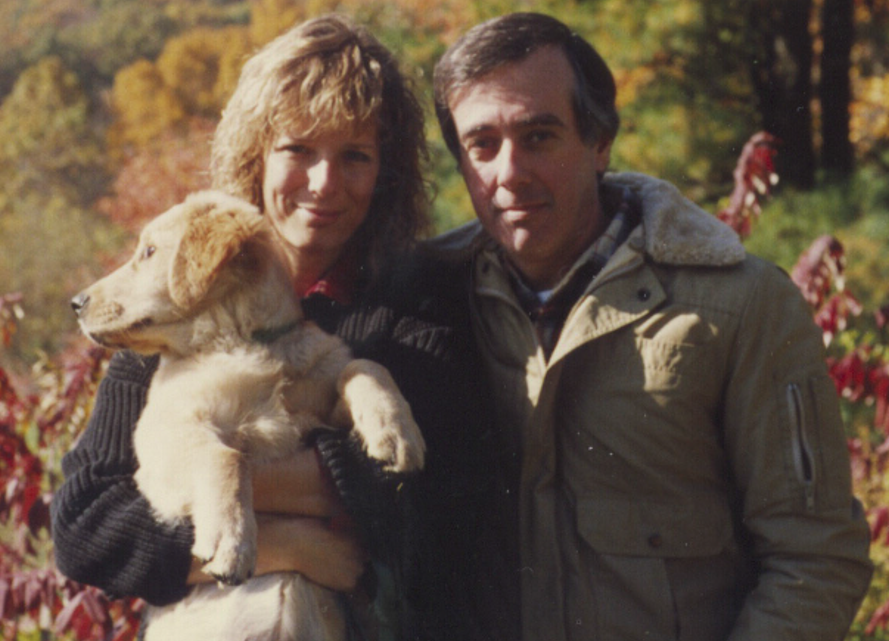

In the summer of 1986, my product manager and I went to Japan for a couple weeks to find a suitable scanner. We traveled all over the country, finally settling on Ricoh, who was by far the most adaptable to our needed customizations. When I returned home, Junell had a surprise for me – Molly, a new puppy! I was not consulted on this and not at all happy about it. But getting that dog turned out to be one of the best things in my life. We’ve had dogs in the family ever since then.

By the fall of 1986, the RMS Phase II program had the bulk of my attention, but Wang’s overall imaging strategy was a bit of a mess. The PIC was still alive, but not well aligned with the future direction. It was standalone, focused on image editing and putting images inside word processing, and it had non-standard image compression. It was soon abandoned. Like PIC, the RMS image workstation was based on the Wang PC, but the company still had the OA-32 project going, renamed 42x, and an IBM-compatible Windows-based workstation in early development called the 11x (released as PC240/280).[17]

[17] Windows was launched by Microsoft in 1985 as a response to the Apple Mac. In those days it was terrible and nobody used it, but Wang – who was one of Microsoft’s largest customers (for DOS) – must have been convinced that it would get a lot better.

The Wang image workstation, I have to say, was better than the competition. PCs back then were so slow, anything to do with imaging required some hardware assistance. To decompress the images required a special $1000 board, saving 5 seconds on image retrieval. MS Windows wasn’t yet usable for our application, so we had our own multiwindow environment, combining image display, database, 3270 mainframe terminal emulation, Wang OFFICE (equivalent to MS Outlook today), and word processing. We had a 200 dpi monitor that was best in the industry, 2000×2000 pixels; it required special ECL chip technology to handle the data rate. The clip below from my status report to Don Dunning in October 1986 summarizes our competitive strengths and weaknesses. I always was interested in competitive analysis, and this helped me later in my career.

The weaknesses having to do with lack of PIC features like image editing and compound document support were not important in records management. Fax and OCR support were my responsibility. They were coming, but not at first release.

The most important weakness, not appreciated at the time, was number 9, lack of workflow support. This was a strategic error on Wang’s part. Wang saw imaging as an electronic file cabinet, where the ROI came from efficiency of document filing and retrieval. It’s hard to imagine today how much paper dominated everyday business activity in the 1980s. It was the way almost all information was stored and communicated, and every office was filled with file cabinets. For documents you created yourself and wanted to share with colleagues within the company there was email, but for everything else it was paper. The mail cart would come by twice a day. That was how information flowed in business.

That meant that the time and effort of filing and retrieval wasn’t the biggest cost of paper. The main cost was the way it slowed the business process. Digitizing paper, getting it inside the computer network, could speed that up by automating the routing of information, and thus automating the workflow. FileNet Corporation of Costa Mesa was the first to realize that. In fact, they even trademarked the name in their imaging product WorkFlo Business System. Wang didn’t understand workflow or didn’t believe in it. It was more complicated, slowed down the sales cycle to emphasize it. That was a strategic error, and I would confront that attitude again and again in my career.

I did not know it at the time, but all was not right with the company as a whole. Against the recommendations of just about everyone, including the Board of Directors, Dr Wang made his son Fred CEO in November 1986, and immediately the business went off the rails. There were layoffs in early 1987 and an across-the-board 6% wage cut. Fred, though, was optimistic:

Fred believed that with imaging technology… the company had developed yet another home-run product, something to rival the epic success of word processing and the VS. The company had made marked improvements to imaging since PIC. It allowed paper-intensive industries such as insurance or the legal profession to store their paper files on easily accessible electronic files. The future of imaging looked very good indeed. And if the technology were to catch on in the way that word processing had, Wang Labs would be out front, for it was one of few companies in the world offering imaging products.

— from Riding the Runaway Horse, Charles Kenney 1993

WIIS

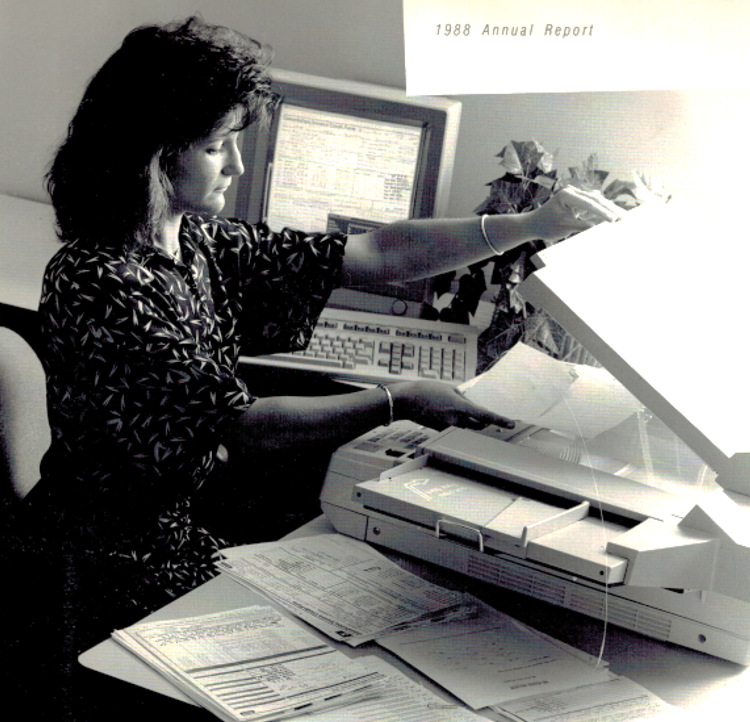

By the spring of 1987 we were ready. We launched our product, now called the Wang Integrated Image System (WIIS), at the AIIM show at Javits Center in New York. The show was twice as big as the previous one in San Francisco. Wang had a big booth, and almost all the hardware in it was mine. It just had to work!

Fortunately, Wang had people with a lot of experience with trade shows, since dealing with the Javits electricians was a nightmare. After setting up all your equipment, you were not allowed to plug anything in. That had to be done by a union electrician, and they were in no hurry. If you did it yourself, they would not only unplug it, they would cut your power cords in two. Basically you needed to bribe them with $100 bills to get power in the booth.

At the show, everything worked great. We certainly held our own against our two main competitors, IBM and FileNet. As a reward, I got Fred Wang’s tickets to see Cats on Broadway. He wanted to go to a hockey game instead. The seats were great; the play, meh.

Helped by WIIS, Wang’s business did pick up in 1987. The press called it a great turnaround, but the Board of Directors was unhappy. They did not believe Fred had what it took to run the company. Dr Wang was undeterred: “He is my son and he can do it!” he reportedly told them.

Fax Gateway

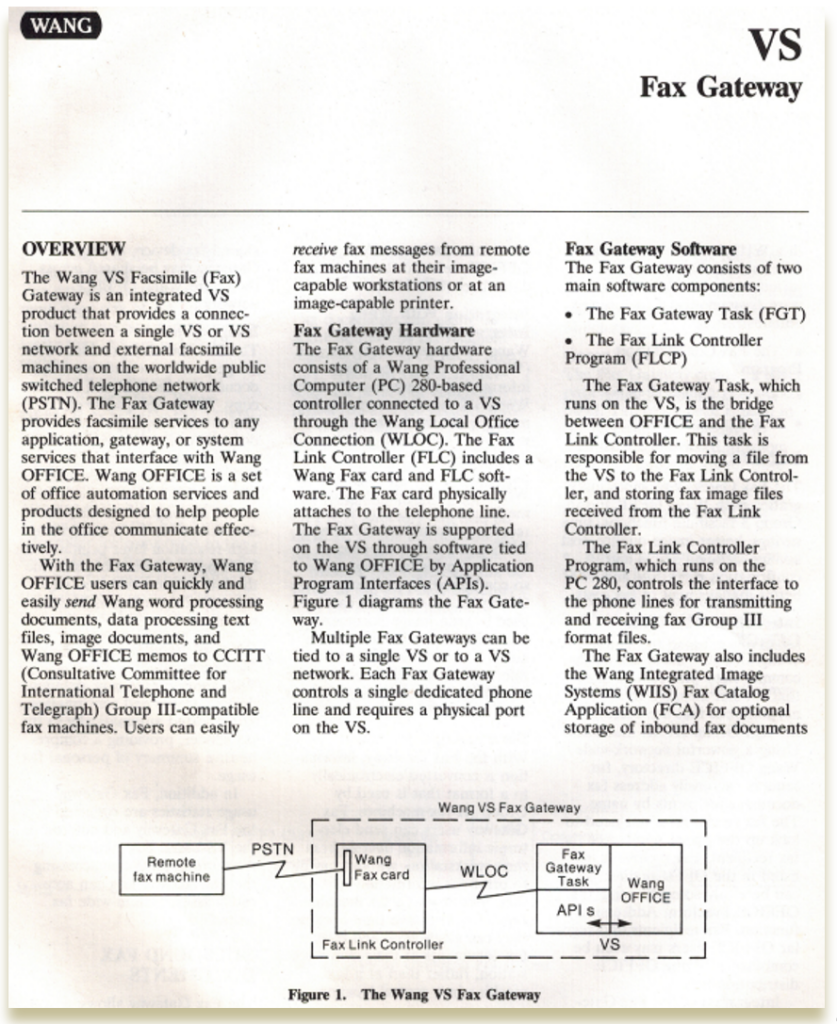

Following the launch of WIIS, I turned my attention to two key missing pieces, fax and OCR. In 1987 there was no Internet. Except for those at select universities and government research agencies, email communication was limited to others within your own company. Wang OFFICE, DEC All-in-One, IBM PROFS all had this limitation. To send a message outside of that boundary, the only wide area network that existed was the public switched telephone network (PSTN) – phone calls! For documents that meant fax.

Fax technology came out of the world of paper. It was developed before word processing, before digital networks. It was paper in, paper out. The paper would be scanned at 200 pixels per inch, compressed using a standard algorithm (the same one we used in WIIS), and sent by a modem over ordinary telephone lines to another fax machine, which would decompress the image data and print out a copy of the paper at the other end. Every business had fax machines; it was the only way.

Now it’s 1987; we have word processing and internal email, but no way to email that document outside of the company. It seems crazy, but the best way to do that was fax: print the document as a digital image file and communicate that using a fax modem either to a fax machine or another computer fax modem at the other end. Today we expect that the telephone network is digital, but not back then. The modem had to translate the digital ones and zeros to sounds of different frequency, called modulation, and then back to digital on the other end (demodulation)… hence mo-dem. The transmission speed depended on the age of the fax machine and the quality of the phone line, so upon initial connection the two modems have to “negotiate” the optimum data rate, again by sending tones. Those are the funny tweeting sounds you hear if you ever dial a fax number by mistake.

Bill Agudelo in my group not only built the fax card but wrote the software to conduct the negotiation protocol. The best part was we integrated it with Wang OFFICE, the company’s mainstream email product. All Wang customers had it. That meant that you could send your email document not only inside the company but to any fax number, and people could receive faxes in their OFFICE inbox. I was very proud of that one.[18]

[18] As an independent consultant in the early 2000s, FileNet would ask me to be a judge for their annual Customer Innovation Award, given for the most innovative use of imaging technology. I can’t tell you how many submissions claimed innovation by integrating fax with their imaging system. I wanted to write, “Are you kidding? That was innovative 15 years ago!”

With the Fax Gateway we could send documents outside the local network as images, but what about binary files? There was still no way to do that. There was an effort underway, however, in the Electronics Industry Association to try to standardize the use of fax for binary file transfer. I joined this so-called TR-29 working group in 1988, because this would greatly benefit my product. I came away from the effort disappointed, actually angry at the way the standards-making process is controlled for the benefit of one or two vendor companies, in this case AT&T. It soured me for years on the whole concept of multivendor standards, which before the World Wide Web in the mid-1990s were quite rare.

Looking back on it now, I see I was naïve and actually off-base in that case. What we wanted was a standard API for sending and receiving binary files. What TR-29 was trying to do was define the handshake protocol for devices to communicate their capabilities, something that would be required before any API could be defined. Chalk that up to inexperience. I was to have many more interactions with standards bodies later in my career.

OCR Server

A bigger effort was needed for OCR. The Kurzweil software we tried with PIC didn’t work very well, but we found another company called Palantir, who later changed their name to Calera. We spent a lot of time and effort together with their engineer Steve Francis to get it to work. (Steve’s path and mine would cross again a few years later.) OCR was configured as dedicated server. WIIS image pages would be submitted to the OCR Server and recognized text would come back.

We released both the OFFICE Fax Gateway and WIIS OCR Server products in 1988. For that I received the Wang Outstanding Achievement Award and got invited to the annual Achievers event. Achievers was instituted by John Cunningham as a vacation to reward the top salespeople. The one in Rome a couple years previous was a notorious blowout. My year was in Quebec City at the Chateau Frontenac. There was a costume ball where we dressed up as 18th century courtiers. It was ridiculous. By 1988, however, Cunningham was gone. Dr Wang later admitted he always hated the event. I think 1988 may have been the last one.

Smart Scanner

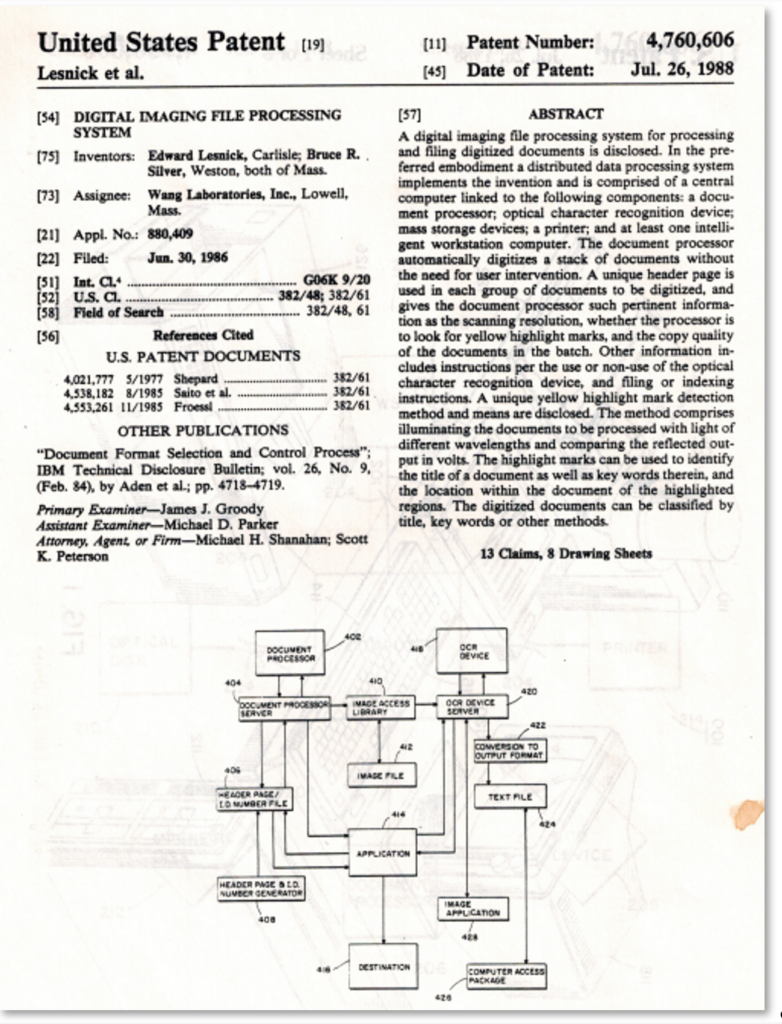

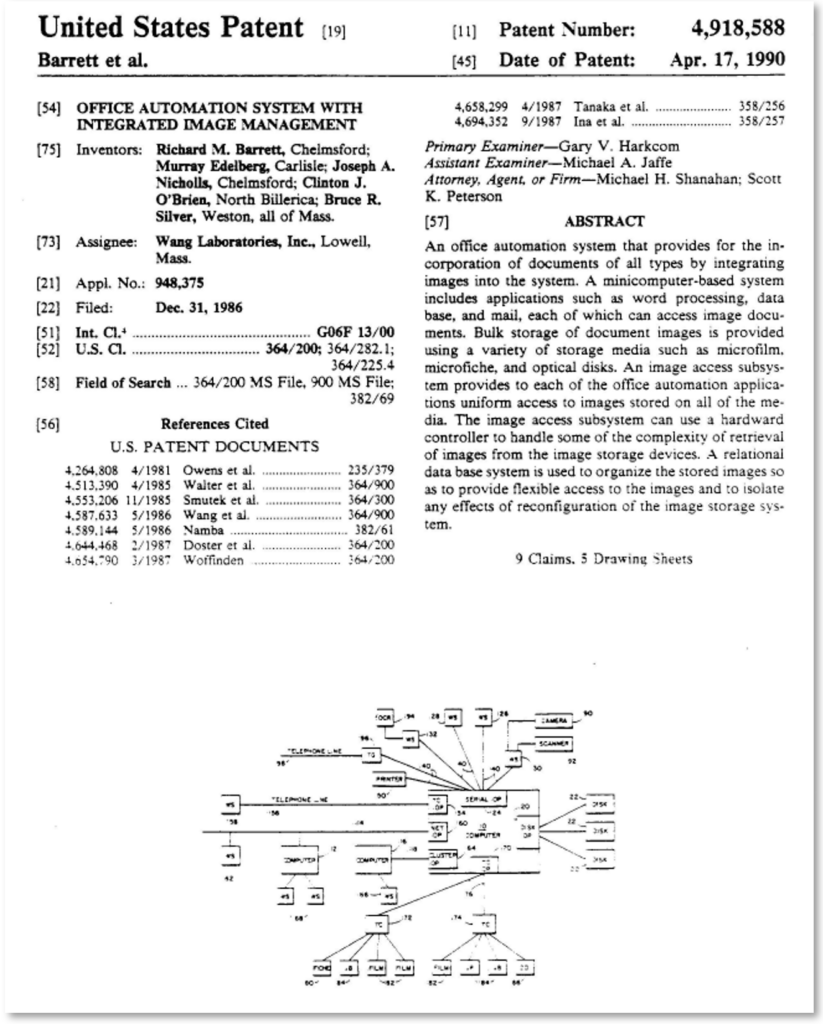

You may be asking, whatever happened to the Smart Scanner and Departmental File System I was tasked with on Wang Day One? The scanner did get built, but not in the way I would have liked. It required two images of the page, one in white light and one in blue light. Comparing the images revealed the yellow highlighted areas, which were used to select the OCR text used as keywords in the index. That part worked, but the scanner required two passes over the page, much too slow! It should have used two sensors and one pass. I don’t know why I allowed it to be built that way, a very bad call on my part. At Polaroid we had topnotch optical and mechanical designers but at Wang just so-so mechanical engineers and I let mine do it his way. In any event, we got a patent on it, although I was surprised to see Ed Lesnick’s name – he was just the guy who said “Wouldn’t it be great if you could…” – ahead of mine on the patent. Things like this have a way of evening out, though, as they did a couple years later.

The year 1988 was the first time I felt I had accomplished something significant professionally. I was responsible for getting a bunch of products out the door and I had done it. I was 39 years old.

Japan with Dr Wang

But once again, the company was on shaky financial ground. Recall that Dr Wang did not want to issue more stock, preferring to finance operations with commercial paper, i.e., debt. In 1988, Wang was negotiating $600 Million of revolving credit with a consortium of banks, but one bank would not sign the agreement unless the Q4 numbers looked good. It turned out they were not good, a 97% decrease from Q4 1987. The company was actually in peril, but Fred remained oblivious and optimistic.

Like most employees, I was unaware of the financial issues, and I had work to do. After PIC, WIIS was not the only imaging product at Wang. An engineer named Steve Levine had a team hidden away in a dark corner of Wang working on a skunk works project called Freestyle. Freestyle was one of the first examples of a pen computer. Instead of a keyboard, you wrote on the screen with a stylus. Freestyle was a desktop device, but a laptop-sized tablet version was also in development. Steve was a flamboyant guy and he put some people off, but his engineering team was first-rate. The Freestyle prototypes were innovative and quite clever in many respects. I wasn’t part of the project except as a resource to include a fax device in the product.

They had already picked a fax provider, Brother from Japan. In early 1989, Steve and I went over to Japan to visit Brother as well as Ricoh, our WIIS scanner supplier. This would be my fourth and last trip to Japan in the 1980s. To me, Japan was always a strange experience, like Lost in Translation (without the Scarlet Johansen part). This trip, though, would be special because Dr Wang was going, too.

Steve and I went over on commercial jet and had our meetings. Dr Wang flew over on the company jet and met us in Nagoya. In Japan, An Wang was treated like royalty. At every stop there was ceremony and a formal banquet. At one I recall we were served a bowl with little minnow-like fish swimming around and a smaller bowl of vinegar on the side. The object was to pick up the live fish with chopsticks, dip it for a few seconds in the vinegar to slow down the wiggling, and then swallow the fish alive. You had to do it or bring dishonor. I made sure the fish stayed in the vinegar until it stopped wiggling completely.

After the last one of these, one evening we all took the bullet train to Tokyo, 200 mph and quiet as a whisper. At the Tokyo station we were met by a stretch limo and whisked to our hotel, the Okura again – 4 for 4 in my trips to Japan. But this time we didn’t go to the front desk, none of that hoi polloi stuff. Straight to a private entrance, elevator to the penthouse floor. Dr Wang’s suite must have been 5000 square feet, unbelievable. The rest of us had regular hotel rooms down the hall. It was 10:30 at night, and I was beat after a long day. But the phone rings. Dr Wang wants to go out for Chinese noodles! He had Harry Chou, Vice Chairman of Wang, with him and one or two other Chinese cronies. This was how they rolled. So off we go, 10:30 at night, to some dive Chinese noodle shop with a bottle of Scotch in a paper bag. We ate noodles and passed the bag of Scotch around the table.

Going home, I got to go on the company jet, a Gulfstream III, state-of-the-art at that time. I had flown out of Narita three times before and it was always like any other international departure, standing in a succession of lines for this and that before you board the plane. This wasn’t like that. From the time we got out of the limo until we were wheels-up in the air was no more than 5 minutes. Out of the car, down some stairs, a special route through the basement, onto the tarmac, a quick ride out to the plane, and we’re airborne. That is really the way to fly. And the flight attendant asks you how you would like your omelette and actually cooks it on the plane. The G3 cruises at over 40,000 feet and flies faster than a 747. We stopped in Anchorage to refuel late at night. The whole Wang Alaska office was there on the tarmac and presented Dr Wang a large freshly caught salmon. So it was that kind of a trip. I got to sit in the copilot’s seat when we landed at Hanscom Field.

I’m guessing this was February 1989. Here is what I did not know until reading Riding the Runaway Horse. Dr Wang had been a smoker all his life. In January, his throat began to constrict and he had trouble swallowing, but he delayed checking it out until he returned from this Japan trip. In March, he found out he had esophageal cancer. He had chemo and was scheduled for surgery in July. It was kept secret. Almost no one knew.

Operation Customer

Meanwhile the company’s credit line depended on the Q1 1989 results, but that quarter was a disaster. Wall Street was expecting a small profit, but Wang announced a $63.7 Million loss. The banks were freaking out. Bankruptcy was possible. Dr Wang was dying of cancer, and Fred was in way over his head. The board tried to bring back John Cunningham, but Fred wouldn’t allow it. In August 1989, Fred was removed as CEO. In his place they brought in Rick Miller, an outsider, basically a stone-cold killer.

Miller needed to reduce operating costs right away. He sold the plane, the European HQ, the Wang leasing companies. And he laid off lots of people. Wang had 32K employees in 1988; by the end of 1989 it was under 23K. A whole bunch of VPs, including my boss Don Dunning, creator of the OIS, were gone. I was still employed but no longer an engineering manager. It was time for Operation Customer, fashioned after Mao’s Cultural Revolution. The problem, said Miller, was that engineers didn’t spend time listening to customers. That was true, probably, and by design, since the last thing any account exec wants is truth-telling from some engineer. Spending a bit of time in the field would actually be beneficial, but to make that the whole job, as Miller did, was just a way to get employees to quit without paying severance.

They called it Application Engineering. I was assigned to the Government sector, headed by Paul Demko, formerly the Engineering VP in charge of networking, a very successful part of Wang technology. I learned about ways that state and federal agencies used Wang products. I spent a week in Hartford visiting agencies of the State of Connecticut, a big Wang customer. In early 1990 I spent a week in Dublin visiting agencies of the Irish government. That was actually a lot of fun. While I was in Ireland, Dr Wang died. There was a beautiful memorial service for him at a cathedral in Dublin, as there was all around the world.

After I returned, a patent on the WIIS system was awarded and I was surprised to see I was one of the five named inventors. It had been filed in 1986, a few months after I inherited SK Ho’s engineers and products, and I had no involvement in the patent disclosure, typically a lengthy process. Honestly, I didn’t deserve it, but it did make up a little for the insult of Lesnick’s name leading the Smart Scanner patent. Five years later, Wang sued FileNet based on this patent. My files were subpoenaed and I was deposed by FileNet’s attorneys. That was a pain in the neck, but I did retain a record of the case, which contained some of the early WIIS planning documents – a good thing, since my regular files on Wang work were thrown out long ago.

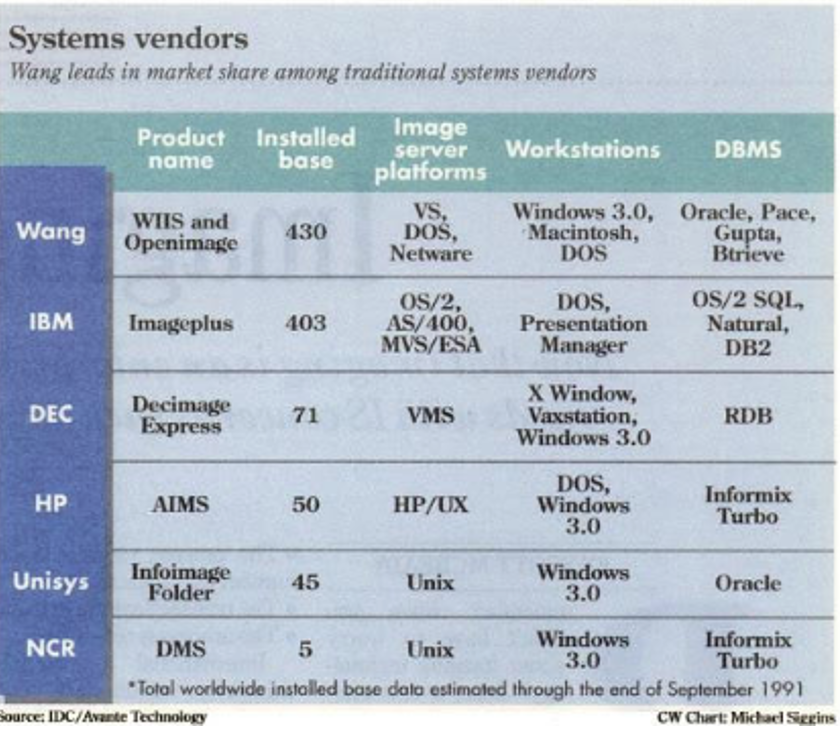

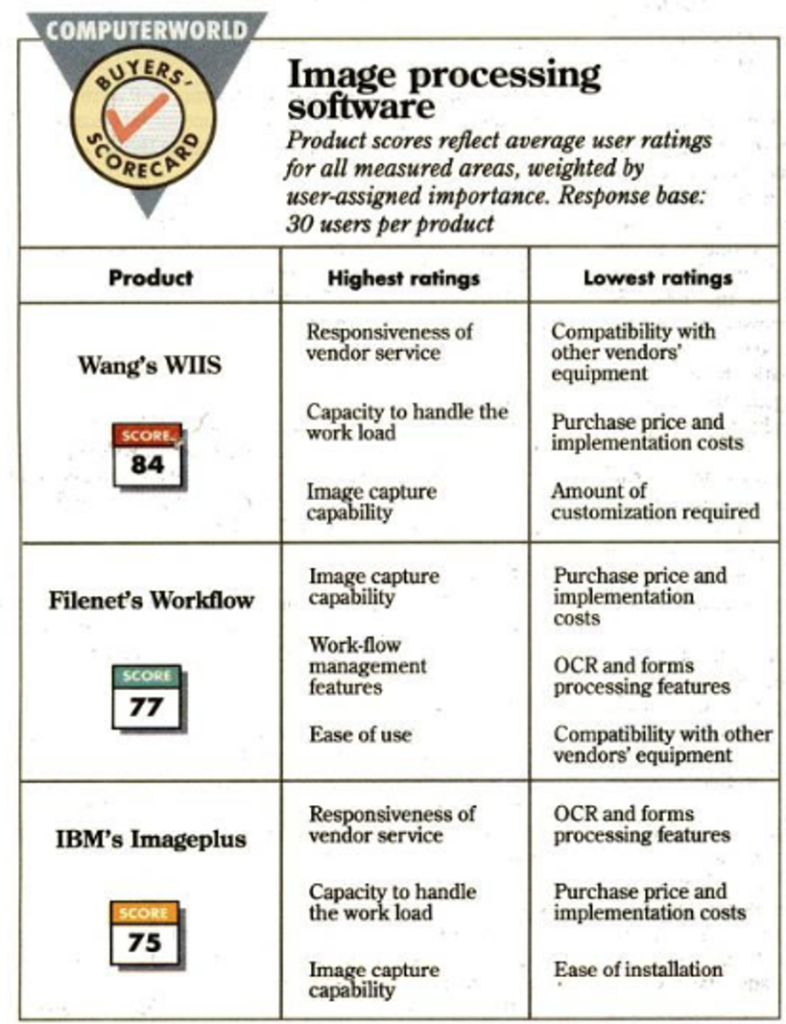

Even though Rick Miller thought the VS and products like WIIS were the problem, they were actually succeeding in the marketplace. The figures below from Computerworld in 1991 bear this out.

When Rick Miller arrived at Wang, the writing on the wall was clear: I needed a new job. I had started looking around in the fall of 1989. I heard about an opening for an industry analyst to cover document imaging at Meta Group in Stamford, Connecticut. I drove down to meet with their CEO, Dale Kutnick, who had recently left Gartner Group to start Meta. Dale was a smart guy but a showoff and a bit of an asshole. My interview was conducted while he was on an hour-long conference call with a client. He would pretend to be listening to the client while he was conducting the interview. It went well enough that he invited me back a couple weeks later to give an overview presentation on the state of document imaging.

I found that presentation recently in my files. It was over 100 pages, which is 3 hours or more, a lot of material. But I knew a lot about the topic. In those days video projectors were rare; hotel A/V had them for conferences, but small businesses and regular people like me did not. Instead we used overhead projectors, for which each slide was printed on a page-sized clear plastic sheet. That was the format for my presentation, which I delivered to Dale and a bunch of Meta service directors. I thought I did a good job, but I stumbled on one question Dale asked me: What was the cost per megabyte of optical disk storage? It was a fair question, but I wasn’t prepared for it. Did he mean cost of the media? The cost of the drive? The cost of the jukebox? The cost of the whole system, including software? I knew too much, and I thought about it like an engineer, not an industry analyst. The right answer, as I would learn, is just to give a number, sound authoritative. It doesn’t matter if it’s right or wrong. If they ask questions about it, you can go into more details.

They decided I didn’t have what it took to be an industry analyst. I was disappointed, but I believed that I did have what it took and that someday I would become one and kick Meta’s ass. Which I did.